We–The Future Seen Through Craft

Inaugural symposium hosted by the Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries at Kyoto Seika University and Kyoto Kougei Week 2019

Date and Time: 1 September 2019 13:00-17:30 (Doors Open 12:00 noon)

Venue: Kyoto International Manga Museum 1F Multipurpose Video Hall

Karasuma-Oike, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto 604-0846 JAPAN (former Tatsuike Primary School)

Host: Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries, Kyoto Seika University

Support: Kyoto Kougei Week Executive Committee

Cooperation: Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan; Kyoto Prefecture; Kyoto City; Kyoto Chamber of Commerce and Industry

Participation: Free / Pre-registration required

We - The Future Seen Through Craft: On the Publication of the Full Transcript

We - The Future Seen Through Craft: Opening Remarks

We - The Future Seen Through Craft【Part One】Fish Skin as a Fashion Material and the Dyeing Techniques of Kyoto

We - The Future Seen Through Craft【Discussion】Passing the Baton to the Future

We–The Future Seen Through Craft:

【Part Two】For the Next 1000 Years of Handcrafts

Moderator

Takashi Kurata (Philosopher; Associate Professor, Meiji University School of Science and Technology)

Born 1970 in Hyogo Prefecture, Kurata graduated from the Division of Philosophy in the Faculty of Letters at Kyoto University, and received his Ph.D. from the Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies at the same university. He specializes in philosophy and environmental humanities and after working at the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, he was appointed to his current position in 2014. In recent years, Kurata has investigated the conditions of thought in contemporary society through various fields such as crafts, architecture, design, agriculture, and folklore from the perspectives of “localized standard” and “intimacy.” Major publications include Intimité de MINGEI (author, Meiji University Press, 2015), ‘Seikatsu Kougei’ no Jidai (The Age of “Lifestyle Crafts”) (coauthor, Shinchosha, 2014), and <Mingei> no Lesson—Tsutanasa no Giho’ (Lessons in “Mingei”: The Techniques of Unskillfulness) (author and editor, Film Art Inc., 2012). Kurata is a Special Research Fellow at Kyoto Seika University’s Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries.

---

Tsutomu Kanaya (Representative, Cement Produce Design Ltd.)

Born 1971 in Osaka Prefecture. After graduating from the Faculty of Humanities at Kyoto Seika University, Kanaya worked at a planning and production company and an advertising agency before founding Cement Produce Design Ltd. in 1999. Through the company, he brings new ideas to traditional industries and produces innovative products that create new possibilities. Together with over 500 small factories and artisans across Japan, Kanaya has initiated collaborative projects and built networks to support market distribution. Recent publications include Chisana Kigyo ga Ikinokoru (Small Companies Survive) (Nikkei Business Publications, Inc.). Kanaya is a Special Research Fellow at Kyoto Seika University’s Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries.

---

Shuji Nakagawa (Craftsman, Nakagawa Mokkougei Hirakoubou)

Born 1968 in Kyoto City, Nakagawa graduated from Kyoto Seika University in 1992 with a major in Sculpture. Upon graduation, he began his apprenticeship as a woodworker under his father Kiyotsugu (a holder of Important Intangible Cultural Property) and learned the techniques of making ki-oke (wooden buckets), sashimono (traditional wood joinery), kurimono (hollowing out forms from a single block), and wood turning. Nakagawa also created and presented modern artworks made of iron, while working as an artisan for ten years. In 2003, he opened Nakagawa Mokkougei Hirakoubou, an independent workshop in the town of Shiga (currently Otsu City, due to a merger) in Shiga Prefecture. Using traditional ki-oke making techniques, he creates champagne coolers with new and refined design, among other handcrafted products. Nakagawa is a Special Research Fellow at Kyoto Seika University’s Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries.

---

Okisato Nagata (Co-Founder/Planning Director at Te Te Te Consortium)

Born 1978 in Fukuoka Prefecture, Nagata graduated from the Kanazawa College of Art with a major in Aesthetics and Art History. In 2001, while still a college student, he produced swords in partnership with Hermès, which were presented at contemporary art exhibitions including the 6th Istanbul Biennial. He later worked at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa (part-time) and a design production company before arriving at his current position. Nagata specializes in business strategies and product development based on the concept of “crafting craftsmanship.” From traditional crafts to cutting-edge technology, he has been involved in business planning at companies in various fields, to shift existing perspectives and structures to reflect current trends. Since 2012, he has organized the Te Te Te Traders Expo. Nagata is a Special Research Fellow at Kyoto Seika University’s Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries.

---

Takahiro Yagi

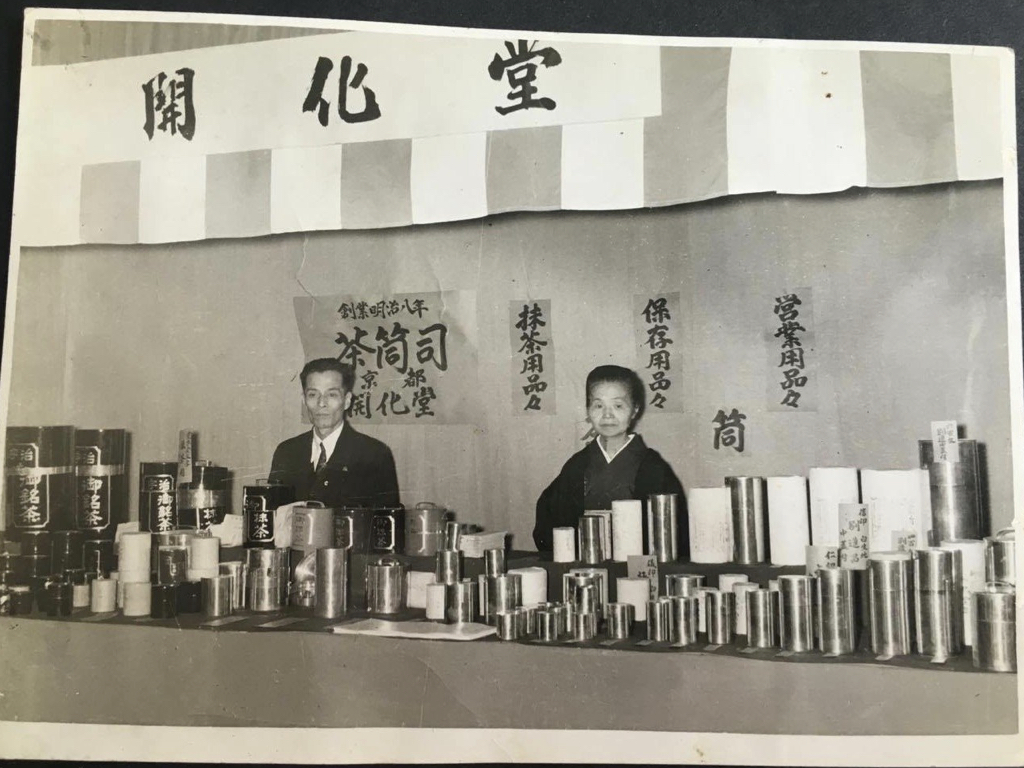

Sixth-Generation Tea Caddy Maker at Kaikado

Born 1974 in Kyoto City, after graduating from university and working at the Kyoto Handicraft Center (Amita Corporation), Yagi took on his position at Kaikado as the sixth-generation tea caddy maker. After training, he took a solo trip to London in an effort to expand overseas sale and promote the family business. He has developed new lines of products through collaboration with designers abroad. He is also one of six young successors to traditional craft businesses that make up the group GO ON, which aims to bring life to completely new and unprecedented ideas. Through his work, he explores new ways for craft to exist, unbound by preexisting concepts. Yagi is a Special Research Fellow at Kyoto Seika University’s Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries.

---

Yuji Yonehara (Director, Kyoto Seika University Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries)

Born 1977 in Kyoto Prefecture. Yonehara is a Kyoto-based writer and journalist specializing in the field of craft. In 2017, he was appointed Special Lecturer at Kyoto Seika University’s Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries. His work focuses on social research and education in the context of craft. Publications include Kyoto Shokunin - Takumi no Tenohira “Kyoto Artisans: The Palms of the Masters,” Kyoto Shinise - Noren no Kokoro “Historic Kyoto Stores - The Spirit of Noren” (co-author, Suiyosha), Listen to the Blues of Artisan in Kyoto (Keihanshin L Magazine), and The Emperor Higashiyama's Enthronement Ceremony in the Edo Period, and Its 1/4 Size Model (co-author, Seigensha).

Note:

The Japanese honorific "-san" is used throughout the text in place of Mr./Ms.

//////////////////////////////////

■Yonehara: I’d like to start by talking about the pieces you see on this long table. These are the works of Shuji Nakagawa and Takahiro Yagi, who will be speaking in this second part of the symposium. In Nakagawa-san’s woodwork, Sugimasa-awase tray (made by joining vertical grain pieces of Japanese cedar), the beauty of the wood itself is striking. We placed the wood shavings produced in the carving process on top of the trays to express the idea that human hands can enhance such natural beauty.

For Yagi-san’s tea caddies, we had him lay out caddies of the same material made in different years to convey the beauty of aging. We wanted to show how the passage of time nurtures beauty.

■Kurata: The title of this panel is “For the Next 1000 Years of Handcrafts,” which I first thought was a typo. I presumed it was meant to be “100 years,” but I realize now it is intentional because we are in Kyoto (Translator’s Note: Kyoto was Japan’s capital for over 1000 years and is sometimes referred to as the “thousand-year capital”). Another message may be that we should maintain a long-term view of issues like sustainability and the environment, which have been brought up repeatedly today. I think all the panelists for this session have opinions about this topic, so I’m looking forward to the discussion.

In this second part of the program, we have six speakers, including myself. Although it has a grandiose title, the aim of this session is to consider the role and possibilities of crafts from a broader societal perspective.

The first theme of discussion is “Craft as Culture—Craft Within the Economy.”

When we think about craft, there are two aspects to it: the traditional, cultural implications, and the question of their future potential as an industry. Both are important, but first, I’d like to ask Nagata-san to share some ideas inspired by this topic.

Craft as Culture – Craft Within the Economy

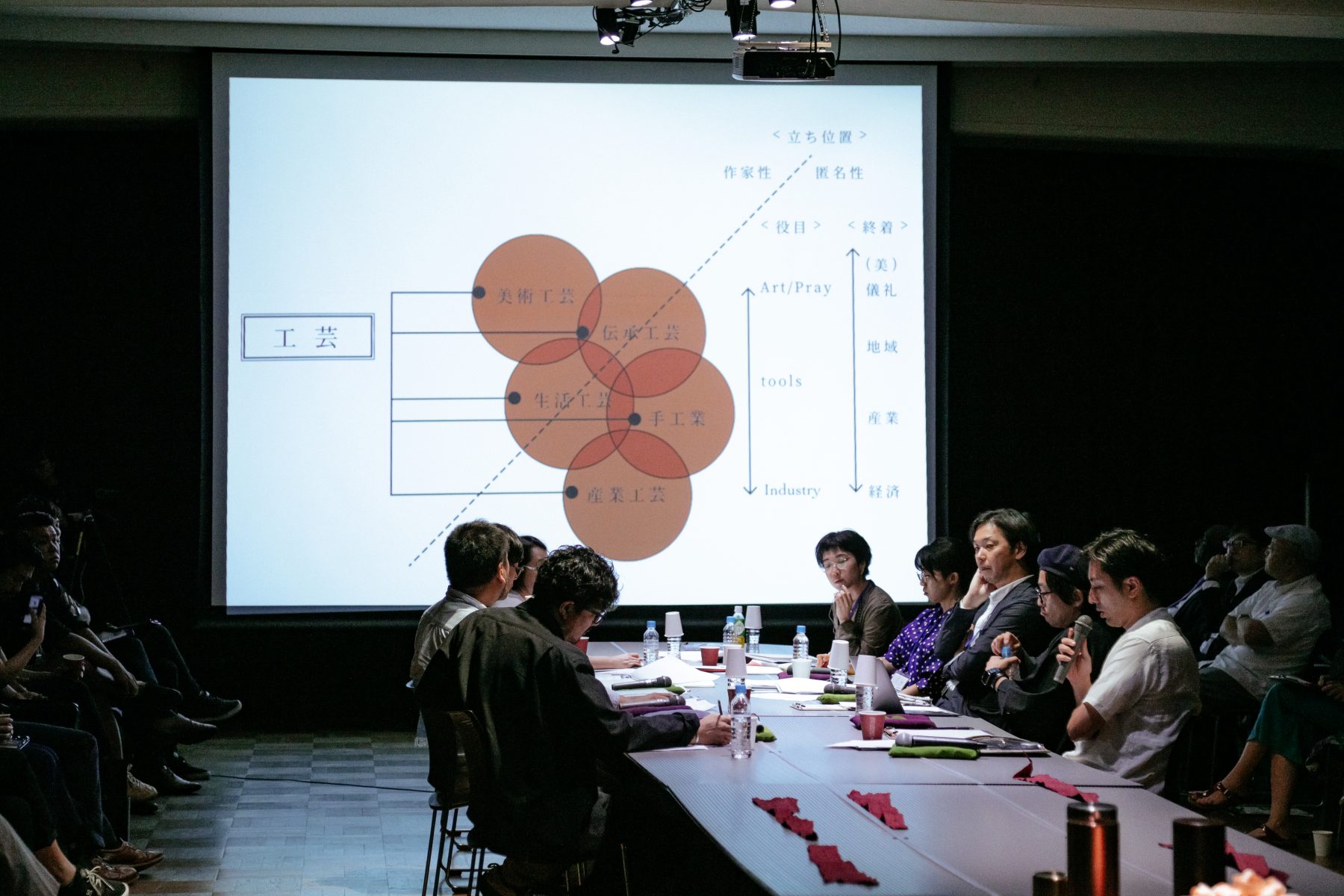

■Nagata: Together with everyone here, I’d first like to analyze the current state of craft. To do that, I’ve created a diagram based on my thinking that there are actually all kinds of subcategories that form the foundation of the word “craft.”

Seated in front of me, we have Nakagawa-san who makes oke (buckets), and Yagi-san, who makes chazutsu (tea caddies). They are makers of “items embedded in daily life.” We also have those who create “artistic craft” full of meticulous techniques. And then there are makers in the field of “traditional craft” who create items for matsuri (Japanese festivals) and the like, where it would be seen as a problem if forms and techniques were to change.

In addition, there is shukogyo (literally hand-craft) or “industrial crafts” for making craft products at a slightly larger economic scale, which are being sold at various shops in recent years.

This diagram includes crafts that support regional economies and culture, are made for offering rituals and prayers, and express an artist’s own sense of beauty. I have divided them broadly into five categories.

I personally have thought about how each of these crafts will continue into the future, and I think that everyone gathered here today have also thought about this from their respective viewpoints.

■Kurata: What’s the difference between shukogyo and industrial crafts?

■Nagata: In my mind, I differentiate them by scale. Industrial craft can create jobs for nearly 10,000 people as a region, with individual companies operating at the scale of 50 or 100 people like in Seto and Hasami (regions in central and southern Japan known for pottery). On the other hand, when we talk about shukogyo, there may be five people per workshop. It’s at the scale where you need to employ more than just the family members. But they are still too small to be considered a regional industry.

I wanted to parse out what become ambiguous when craft is described by just two Kanji characters (工芸), in the term kougei (craft). There are all types of crafts that fall under this category. And on top of that, we are assigned the timeline of the next 1000 years for this discussion. It’s a little too far off for me to grasp, but I want to hear everyone’s thoughts on the futures of artisans.

■Kurata: Next, I’d like to ask Kanaya-san to talk about design and ownership.

■Kanaya: My job involves providing on-site product development support for small factories and craft workshops. In my experience working with anywhere from 500 to 600 companies, I have noticed a tendency for artisans to try and overcome difficult situations by relying solely on the development of their own skills. Today I want to introduce a craft workshop that is working to establish sustainable management. I think the challenge in the field of craft production is that someone has to make a sacrifice in the process. This workshop is trying to resolve this issue through improved management structures.

■Kurata: You seem really excited for today, all dressed up in kimono!

■Kanaya: This kimono is actually made by the outdoor apparel and gear brand snow peak. I think it’s a recent trend that companies in these newer areas are coming into the field of craft.

I’d like to start by sharing an example.

This is Hanashyo, an Edo-kiriko (Japanese cut glassware) company based in Koto Ward, Tokyo. Originally, Hanashyo was a subcontractor for a major glass manufacturer. But when the manufacturer went bankrupt, Hanashyo switched to planning, manufacturing, and marketing products in-house. In 1997 (the early days of the Internet), Hanashyo was already selling their products online. Initially they had a very small store, if you could even call it that. They were making sales out of a small meeting room on the second floor of the workshop. But because of the of the company’s consistent and proper management of the sales records, they now have a brick-and-mortar store in Nihonbashi.

This company is also very mindful of intellectual property.

It’s rare for craft practitioners to register their patents and designs as intellectual property, but this company named their original techniques and the new cut glass patterns (designs) created using these techniques, and what’s more, they acquired the rights to them. Hanasyo obtained design rights and trademarks so that other Edo-kiriko glassware artisans cannot use these names.

Furthermore, the company utilizes these intellectual properties to develop products that are not cut glassware such as candies, iPhone cases, origami, and tenugui (hand towels) to name a few. Edo-kiriko is an expensive luxury product, so most of the customers at the Nihonbashi store are shopping for themselves and not looking to buy gifts. On the other hand, there is still a demand for souvenirs. This is where the intellectual properties are put to use, to make souvenir products in a lower price range, suitable as gifts to give away for domestic or overseas visitors.

What surprised me most about this company is their human resources development.

It is said that it takes 10 years to be fully qualified in this field. But by opening up the entire workshop to the public, they devised a teaching method that trains staff to be able to do most of the work in just five years.

They also use this curriculum to run a school for learning Edo-kiriko glasswork. In other words, the cost of staff training is covered by tuition from people who want to try their hand at the craft. Additional training and a system for educating artisans are also built into this school and the company recruits employees from the graduates.

Because of this system, there is a need to constantly innovate Edo-kiriko techniques. When I first learned about this company, I was blown away. They address the challenge of craft production, not with products but with creative management.

I felt that even a technique can become a “product” if you acquire the rights to it. And given a structure, the training process itself can also become a product as a new form of craft education. In every industry, there are purist ideas about how things ought to be, but I feel the importance of shifting towards new concepts, to both think and act.

■Kurata: Yonehara-san, I think it was a mistake to put me in the role of a moderator today! Hearing stories like this, I can’t help but move over to the side that asks questions.

When thinking in terms of profitability, I can certainly see that they’re doing very important work. On the other hand, in the realm of craft, there is a kind of…shall I say a sense of co-ownership? If artisans are trying to outwit each other, I think it can turn very ugly.

When I used to work at a research institute for environmental issues a long time ago, they posed the question, “to whom does the forests belong?” The forests are the commons—we need to think about how to preserve them precisely because of its shared nature.

And I think that connects to today’s theme of “we.” When thinking from this perspective, I’m a little concerned that initiatives related to intellectual property rights start to become a fight over ownership.

■Kanaya: What do you mean by that specifically?

■Kurata: For example, it all starts to sound like they’re saying “this is my territory, so stay out.” Although this expression might not be the most appropriate…

■Kanaya: In that sense, I thought it was really interesting that Hanashyo’s education is open to the public. Craft companies commonly train artisans exclusively in their workshops, and expect apprentices to keep working at the company, but Hanashyo is different.

Not all of the students who complete the course go on to work for Hanasyo. There are some graduates who open their own businesses. I think this initiative helps the whole of Edo-Kiriko industry to thrive, considering that staff training is the biggest expense.

■Kurata: I kind of played devil’s advocate earlier, but what are the incentives for registering trademarks?

■Kanaya: I think it’s important to register original, newly developed techniques as intellectual properties and protect them as assets. Of course, there are fees for registration. But it’s not a lot. For example, out of design rights, patents, and utility models, the registration fee for a design right is about 30,000 yen. At this price, even the smaller companies can afford to retain design rights, so I think this is a good starting point. In 2019, the Japan Patent Office amended the Design Act, which significantly increased advantages for makers and craft practitioners. While it costs a little more for utility models and patents, I personally think they are worth applying for.

In the past, our company has experienced cases in Kyoto where lookalike products appeared on the market. If you haven’t registered, you can’t litigate. Under the Unfair Competition Prevention Act, you can assert your rights to something you created without a registration, but only up to three years after you’ve made it. Once those years have passed, you can no longer make that claim.

The rights could end up with whoever registers the product three years after it enters the market. For those of you who develop new techniques, if you register them, they become assets to the workshop or company. And when other workshops and companies use that technique, it will generate royalty income and broaden the business. In particular, if you are expanding your business internationally, I think it is better to be aware of these rights-related issues.

■Kurata: I imagine there’s more to say about this topic, but I’d like to ask each speaker to take the previous theme and move the discussion forward, like we’re passing a baton.

■Yagi: I was given the prompt “Products have long lifespans.” Concerning intellectual property, apparently there were fake Kaikado products on the market when my grandfather ran the business (TN: the counterfeit brand used 花, a different but homonymous kanji for the syllable ‘ka’ in ‘Kai-ka-do,’ instead of the authentic 化). In our case, my grandfather simply said “now that there’s a fake, our tea caddies have become the real deal” and just let it go.

That’s how common tea caddies are, I suppose.

Products live a long time. In fact, they live longer than we do, so I think it’s important to think about how to convey their original value, and how to pass it on to future generations.

This photo shows tea caddies as they age. The black tea caddy over there (on the table) is just over 100 years old and it was originally a silver-colored tin tea caddy. It’s a distinct characteristic of our company that we’re still making the exact same things as we did 100 years ago.

I’m part of a project called GO ON, and Hosoo-san (Hosoo Co., Ltd. / Nishijin brocade), a fellow member, often shares this memorable quote by Winston Churchill:

“The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.”

Today’s theme is “1000 years.” 1000 years ago would’ve been around the Heian period, roughly speaking. I think there’s value in thinking about the present from that point in history. For us, we think about the present day from the point of our century-old tea caddies. Or, we imagine that our customers today might bring their tea caddies back to us in another 100 years for repair.

What do we need to do to prepare for that moment? We need to pass down our identity as makers. What makes us uniquely “Kaikado” isn’t words, but something that is imparted over tine in everyday life.

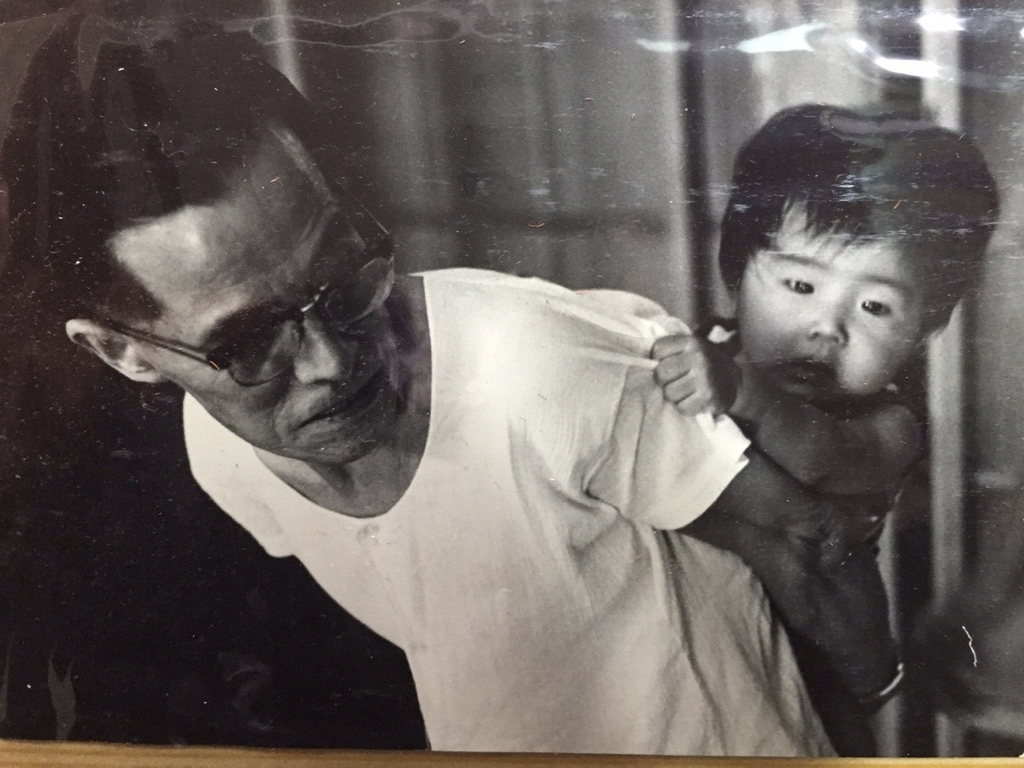

There’s a cute kid in this picture. That’s me. I’m being carried on my grandfather’s back.

This is a photo of my son playing with my father.

It may be these moments of daily life that carry on the unique identity of Kaikado or “Kaikado-ness.”

I think there’s one more important thing and that is to communicate.

For our customers and the people who use our products, I believe we need to present something that changes with the times, not just tea caddies. At Kaikado, that means opening a cafe, or designing caddies for coffee beans and pasta. We are branching out and making a wide range of items as a way to draw attention to our main product, the tea caddy.

In this way, I continue my practice with a view to the future, even after I die. Perhaps these are the efforts that lead to carrying on the craft over a long timeframe, which links back to today’s key concept of “we.”

■Kurata: I think this actually connects to what Kanaya-san was saying earlier. It may sound like his talk was more on the side of business, while Yagi-san’s talk included cultural aspects. But after giving it some thought, I see that their efforts are simply different approaches to preserving the things that are most important to us, that will live a long life.

My takeaway from Yagi-san’s talk just now is that if we don’t take active steps to keep what matters most, even the things that need to be preserved will be lost—just because you’ve been making the same thing for a really long time, that doesn’t mean it’s fine to keep repeating it aimlessly.

This conversation can’t be neatly split into the topics of culture and the economy because the two actually tie into each other organically.

That is to say, we are talking about something that will be shared across generations, not something privately owned that is contained within one’s own lifetime.

Of course, educating our contemporaries is important but what seems to be in question here is diachrony or continuity across time and across generations.

Thank you. Everyone has spoken so eloquently that I’m starting to feel the urge to stir things up a bit.

Now I’d like to hear from Nagata-san again, this time on “Building an ecosystem for craft production.” (TN: “craft production” is a translation of monodukuri literally “thing-making,” a broad term frequently used during this symposium to denote the industry of making things from artisanal handcrafts to mid-sized manufacturers)

■Nagata: The topic of diachrony came up just now, but what I’m about to say may have more to do with synchrony or even instantaneity, depending on the situation.

One consequence of our pursuit of rationality and efficiency in the last 1000 years and particularly the last 100 years, is that we’ve arrived at a state in which what we call “craft” has been left behind, no longer able to catch up with machine industries or information industries.

I wondered, in these times, should Craft try to solve its problems in ways similar to industries that extol rationality and efficiency?

Perhaps you could call it “embracing” the problem instead of solving the problem. For example, maybe there’s a way to see scaling down (financially) as a good thing because then there would be less people you have to attend to.

Instead of going through the trouble of expanding in scale at this moment, I wanted to reevaluate the size at which we can survive, that also values and is aligned with our current conditions. I organize something called the Te Te Te Traders Expo. This event gathers makers from different regions—some of whom are practitioners of traditional craft, others are makers operating at a similar scale but in different fields of manufacturing—and connect them to buyers and consumers. We created Te Te Te as a place for tsukuri-te (makers), tsukai-te (consumers) and tsutae-te (communicators) to come together. Here, we explore ways of continuing our work that only we can, without being influenced by concerns about the scale.

For a major industry, when peers gather, the conversation usually turns to complaints or talks of jealousy. If two people are from the same region, that means they both have shared business interests, which makes it difficult to speak to each other frankly.

This is why we specifically choose people from different industries and different regions to gather in one place and encourage the exchange of information and wisdom. We call this “linkage” instead of a “solution” and our work is to make a place to build connections and relationships.

Up until now, conversations about traditional industries were dominated by the narratives of consumers, produces, and manufacturers, but I feel that there is one more important group: tsunagi-te (connectors). As we look toward the next 100 or 1000 years of traditional industries, I think their role will become all the more necessary.

■Kurata: Were there any particular thoughts or ideas that went into the word “ecosystem” in the discussion title?

■Nagata: We can think of Craft as having the same industrial scale as the automobile industry, but nothing else is the same when it comes down to the economic units, life cycles, and operations. This is why I felt the need to consider a different life cycle for Craft. The time frame is also different, isn’t it? Regarding what lies in the background of a business, while Kaikado makes products that carry its history from 100 years ago, people working in IT are detached even from what happened last year because they are looking for ways to change tomorrow’s society.

It’s fine for these different time frames to exist, but I believe today’s Craft has the potential to recreate its own unique ways to support, communicate, and preserve what matters.

■Kurata: I think an ecosystem is essentially a type of network. As exemplified by the division of labor, the world of craft is inherently a series of interdependent connections. In your work to form the Te Te Te Traders Expo and the new players that gather there, as a place for, or as points of connections, I imagined there was an intent to reweave the existing traditional network, which had lost its relevance and functionality as a system.

■Nagata: Yes, that’s a part of it, too. I would also add, until around mid-Meiji (T/N: the Meiji period lasted from 1868-1912), these connections and relationships existed within a radius where goods could be delivered in a day or two. That’s why similar sets of industries can be found across regions. (Because goods could not be conveniently delivered long distance,) there are about 86 regions known for urushi (Japanese lacquer) crafts in Japan, and that’s only counting the ones still remaining today. People practiced a set of crafts in each respective region. But now, with the advancement of distribution technologies, we live in a time when you can transport goods to Brazil in 24 hours.

Compared to when craft was a thriving industry, the interaction distance between things, information, people, and thoughts has changed dramatically. And because of this change, I believe new ways of connecting are available to us today

■Kurata: Is Te Te Te Traders Expo a place for networking that includes overseas participants?

■Nagata: Yes. One of our members is in charge of overseas distribution, specifically of handcrafts. Currently, our team is connected to about 400 stores in 25 countries, to which we sell wholesale, send information, and so on. We’ve built a network that extends as far North as Moscow and St. Petersburg and as far South as Cape Town.

■Yagi: Whether you are making or selling, I think it’s extremely important to pay attention to the fun parts of craft. Looking at the photos (of Te Te Te Traders Expo), it looks like a really fun atmosphere. Is there anything you plan behind-the-scenes around this aspect of “fun”?

■Nagata: I would say, going out for drinks together. I think it’s crucial to talk frankly. Wisdom is something that should be shared. For example, in the food world, people will share a recipe that someone developed, others will adapt it and it will keep spreading. But we remember to credit the original recipe developer, and each time it spreads further, we acknowledge that it is an adaptation. When it comes to expanding through “linkage” in this way, how positive of an outlook the makers have, and how much they enjoy the work—as Yagi-san pointed out—are key. Instead of struggling and bearing the difficulties of the industry, it’s about fully opening up to new possibilities.

■Yagi: I also want to ask about customer relationships: what do you keep in mind when it comes to the fun in customer experience?

■Nagata: Actually, in just two weeks, we’re hosting our Te Te Te All Right Market. Normally, a market is used as a place where makers communicate with consumers. But at this market, we’ve requested that the vendors are the ones to listen. For example, they might ask their customers, “What drew you to pick up this product?” or “What do you wish it could do?” We conceptualized this event as a space where the makers can hear from the consumers, and the consumers can share their thoughts with the makers. There are plenty of books about the makers’ thinking that underlie their work, but there are none that document the consumers’ thoughts and voices on how a product could be improved. There are no places for that, either. That’s why we plan to create more spaces like this in the future.

■Kurata: I think your last point about fun and joy is very important and it applies to other topics discussed today like sustainability. We’re trying to address “how society should be” or “how the environment surrounding craft should be,” but for a consumer, it’s unlikely that they would be moved to sympathize with these issues or take action if they have to make compromises. That’s why having an element that people feel naturally drawn to, whether that’s something enjoyable or beautiful, is essential. These are the biggest selling points in craft. Sometimes you explain the appeal with words, and of course there are important stories to tell, but there is abundant joy that more than supplements those stories, and this connects back to the discussion about finding new ways of conveying the joy to the audience.

Manufacturing and Society

■Kurata: I’d like to move on to the next topic.

As we continue the thread from our previous discussion, I’ve assigned “manufacturing and society” as the second theme. Earlier, the speakers each shared a story from their current work and undertakings, touching on the aspects of culture and economy within the narrow context of craft. If we zoom out a little to look at the bigger picture, I think we might start to see what manufacturing (translated from monodzukuri – see note above) currently can and should do in our society. This includes examining the perspectives unique to the field of craft on this issue. First, we’ll hear from Nakagawa-san on his experience of craft overseas.

■Nakagawa: I’m a graduate of Kyoto Seika University and during my time there, I majored in sculpture. I was sculpting in metal to make “contemporary art.” I was born and raised in an environment where the family business was crafting ki-oke (wooden buckets), and now I work as a ki-oke craftsman.

In the past few years, I’ve experienced a significant increase in the amount of opportunities I have to present my ki-oke, mainly overseas.

For the past two decades since 2000, I’ve also noticed a dramatic change in the way fine art and craft are being treated in Europe.

Up until then, contemporary art was at the top of the hierarchy as the absolute king, especially in European galleries. And craft was all the way at the bottom. There was definitely a vertical structure in place. So back then, if you gave a talk about craft in a gallery in France, no one would listen. That’s the kind of environment we had.

But just in these past several years, contemporary art galleries started to deal in craft. For example, Yagi-san and I participated in an exhibition at the Pace Gallery in New York, which is one of the top contemporary art galleries in the world. Even at a place like this, we are starting to see exhibitions on Japanese mingei (folk craft). There, I had a chance to show a piece I made in collaboration with Hiroshi Sugimoto. The position of craft, which had no place at all just a few years ago, is undergoing a major shift. It’s as if the vertical structure has turned horizontal. Now craft has so much momentum that it feels like it has overtaken fine art.

One of the reasons for this might be changes in the art market. To put it bluntly, it’s about the collectors’ money. I think this is a reaction to the market becoming filled with artworks that are difficult to collect.

The art world started to place an emphasis on installation and conceptual art at the beginning of the latter half of the 20th century. What used to be collectible, material artworks, turned into concepts and spaces. For a collector, I think these works ultimately fail to fulfill their desires for material acquisition and ownership. Some installations are site-specific, which poses the difficulty of the site itself not being available for purchase.

I believe it’s under these circumstances that the money in art is being put into craft. Although it’s not necessarily an evidence of my speculation, but in recent years we’ve seen “craft weeks” popping up in cities around the world.

I submitted an entry to The Loewe Craft Prize, which was first held in 2017. The pieces exhibited here today were selected as inaugural finalists in the prize.

Art prizes and design awards have been around for 10 to 20 years, so why is it only now that awards and prizes are being given out to craft? I think the elevation in the value of craft may be one reason behind it.

Additionally, as a separate trend, there is a government-initiated increase in domestic craft awards with the introduction of subsidies related to the Olympic Games. Both instances can be defined as a kind of boom, but I think the global boom in craft and the boom within Japan have totally different contexts. So my question is, which trend do we need to follow moving forward?

■Kurata: Once again, we’ve come to a fascinating topic of discussion. But I’m wondering why I find this so interesting.

It’s only in recent years that craft has begun to make a comeback and seen a rise in interest, particularly overseas. If we look at contemporary art for example, it has expanded steadily over the past century or so by co-opting what lies outside of its parameters. I think so-called “Outsider Art” may be a good example of this. There’s been a move (on the part of the art world) to constantly excavate new worlds, not of Art made by Artists but of “non-art,” to then drag into its own territory.

With that in mind, one of my concerns is that craft has now become subject to this co-option. Nakagawa-san talked about the collectors wanting to fulfill their material desires, but we can’t ignore the inherent nature of craft, which is that they are tools intended to be used.

Functionality doesn’t have to be the only purpose of a craft object, but I think it’s a point we can’t overlook. What are your thoughts on this, Nakagawa-san?

■Nakagawa: I agree and it’s one of the areas of craft that Nagata-san described in his diagram earlier. My thinking is more or less the same, but I believe that within the broad field of craft, there is an area for collectible pieces and a separate area for functional pieces. The fact that these two areas cannot be merged, is what makes craft what it is. And it’s this diversity that we need to acknowledge as we move on to the next generation.

One other thing I’d like to add is that this shifting trend from art to craft ties into today’s theme of “we” (the title of the symposium).

Ultimately, Art is individual expression. Craft is something that we share. In Yagi-san’s case, his company has been in business for six generations and they can say, “we have been making the same tea caddies for six generations.” Craft can be shared across generations in this way or it can be shared between a customer and a maker in the collaborative process of creating a custom-made piece.

I collaborate with designers as a craftsperson, but my artist friends who see that ask me, “how can you make a work based on someone else’s idea?” For me, it’s not an unnatural thing to do. But for an artist, giving shape to someone else’s idea might be out of the question. Again, this is an example of how craft is closer to the collective expression of “we.”

A second-generation Picasso doesn’t exist. Even if his son were to take over, whatever he produced would still be considered a fake.

But in the case of craft, artisans are succeeded by subsequent generations who carry on not only the techniques but sometimes even the name. I believe this historical context forms the basis of my work as we find ourselves living in the age of “sharing.”

■Kurata: (jokingly) Yagi-san, is it ok that he just took your talking points?

■Yagi: It’s fine, I’ll say a little more on that later in the discussion. But going back to the idea of sharing, if we say that craft is about this sense of “we,” it makes it difficult to think through the issues mentioned earlier, like intellectual property. To what extent do I assert my authorship over something I make? How much do we permit when deciding whether or not a lookalike product is an homage?

■Nakagawa: That’s the part that’s extremely difficult. On the one hand, we have these laws today that safeguard intellectual property and I think it’s very important to assert one’s intellectual property rights, but on the other hand, when thinking long-term, I personally think they are means to monopolize ideas and should eventually be nullified.

■Kanaya: There’s a limit to the number of years intellectual property rights remain protected.

■Nakagawa: 25 years, was it?

■Kanaya: Yes, 25 years.

■Nakagawa: That 25-year period feels a little too long for my pace of work. Even though we are legally entitled to hold exclusive rights over intellectual properties for 25 years, I think what we really need to be doing is feeding back value into society under a different framework. Reshaping the system into one that gives back ideas and techniques to the communities—I think that would benefit the future of craft.

■Kanaya: I would argue that obtaining intellectual property rights is one of the ways that businesses strategize for the future. Some people make their intellectual property public and available for anyone to use. For example, the commonly used word kaigo (long-term care) is actually trademarked by a business based in Sumida Ward, Tokyo. While they own the right to the word, it is now used widely. The word spread because the company allowed others to use it. By the same logic, if Nakagawa-san has a technique that others could benefit from, there is a way make it available for public use through registering it. Sharing widely through such a system could lead to the creation of a more beautiful form and also help improve other artisans’ skills. I think that would be an interesting way to utilize intellectual properties.

■Yagi: On the other hand, I feel that things like design or technique (which are often protected as intellectual properties) tend to be the part that is closest to the surface and the most visible. If anything, I think it’s the part you can’t see—the ways of thinking, the philosophy or background behind the product—that is so crucial in craft. That’s why I believe communicating those narratives in depth and creating a world that recognizes the value of these ideas or stories, is far more meaningful than protecting the “visible” assets. But I’m curious to hear everyone else’s thoughts on this.

■Yonehara: We have a culture of utsushi (noun for “copy” or “duplicate”; also “reflection” as in a mirror) and I think this is one of the characteristics of Japanese craft. An artisan copies a past masterpiece and makes it their own. Historically, craft (in Japan) has been refined through a repetition of homages and customizations. So you can imagine that the concept of intellectual property is still new in the world of craft, and I worry that the idea of turning a design or technique into a completely private possession, wouldn’t sit well with practitioners in the field. On the other hand, there are actual cases of plagiarism in the field of craft, and unlike other industries, there are no established means to protect a work at this time. Because of that, I think it’s valuable to even have a conversation about this, like we are doing today. As for my point about most craft practitioners being trained through utsushi, I’d like to check the accuracy of that statement with the other speakers as we continue the discussion.

■Kurata: I’m glad to see so many different points being raised on this topic. Yagi-san touched on the value of time spent behind-the-scenes on numerous trials and errors to reach the final design, which manifests on the visible exterior. The suggestion that we should turn to these aspects of craft, is highly relevant when it comes to thinking about the essence of kougei (Japanese craft).

Nagata-san talked about the lack of an organized platform for consumers’ voices and ideas, but I wonder if that’s what the consumers are really looking for in this moment. Perhaps what they actually want is to have the makers share the process behind how a product came to be, not the ability to comment on the usefulness of a finished product. If we’re only looking at the end point of the process (i.e., the finished product), a mass-produced industrial item would suffice.

If we take a cup for example, cheaper is better, so you might ask, what’s the difference between a hand-crafted cup and something from the 100-yen store? Well, we’re not just looking at the end result or its versatility, we’re looking at how much of the maker’s “self” has been put into the process leading up to that point. Or, how we can position the consumers as co-producers and involve them in the process. I think that is what’s being asked of us now, and this connects to what Nagata-san was saying about medium-volume manufacturing.

■Nagata: In the old days, I think people were able to figure out how something was made, just by looking at it. When there were still tatami shops in the neighborhood, you would see into the store and think, “that’s how a tatami is made.” Back then, everyone had a kind of object literacy, but these days I hear all kinds of stories, like the one about kids who see pre-cut sashimi at the supermarket and think there are slices of fish swimming in the ocean. When consumers are left with no choice but to rely on the economy to provide them with products for survival, they will need to regain their object literacy.

At a time when we find ourselves asking questions not only about the future of craft but also of humanity and its survival or necessity in this world, I think craft has garnered attention as a collective resource that encompasses history, culture, and even diversity, as well as skills and materials.

Conveying the Context and Value of Objects

■Kurata: Next, we have a story from Yagi-san on the topic of “Conveying the Context and Value of Objects,” which connects nicely to what we just talked about.

■Yagi: As I mentioned earlier, Kaikado has been making the same tea caddies for 100 years. On the other hand, Nakagawa-san seated next to me, has incorporated different woodworking techniques and produced a wide range of pieces in his career. Because Kaikado’s product line has not changed, we’ve instead varied its presentation and audience over the years to survive as a business.

Pictured here are my grandfather and great-grandmother. About two years ago, I came across this photo by chance. When I saw this, I realized that they were trying to do what I do now at places like Maison & Objet in Paris. I find that my inclinations and values resemble that of my grandfather’s, and there are some things we share that connect his generation to mine.

This next part is specific to our product, so I went back and forth on whether to bring it up, but I decided I wanted to share. People often comment on how smoothly and quietly our canister lids lower down. But it’s actually the other way around: when we make the canisters, we pay a lot of attention to the way it feels the moment you open it. Let me demonstrate. (opens and closes the canister)

Even though we put a lot of care into making sure it feels good when the lid is opened, what most people notice is the way it closes.

So, in order to convey the feeling of opening the canister, we worked with Panasonic to create the Kyo-zutsu speaker. Up until now, we didn’t have much choice but to show the lid lowering down (in promotional materials) because it was so difficult to communicate the satisfying feeling of opening the lid in videos or photos. When I consulted the designer about this, they said, “What if something happened when you opened it?”

When I look around the craft world, I notice a lot of people who aren’t fully aware of what they find pleasing in their work, or what their grandfathers and fathers strived for all those years. Looking ahead, I think it will become important to share—in simple but exciting ways—what feels good to you personally, with those who view and buy craft products.

We don’t have to talk about it in complicated terms or publish any more books on the subject. I was at a tea shop in London recently, and the store clerk was explaining to a customer which teas were organic or fair trade and the customer said, “I don’t want to listen to the story, I just want to taste tea!” They didn’t care about the background of the product. All they wanted was good tea and I thought, this is the same with craft.

For us, the most basic thing we have to do is make our work with care. The question isn’t “is it well-made”—that should be a given—it’s “how do we convey that it’s well-made in simple yet exciting terms?”

The answers to that forms the root that supports the act of making. I think we’re living in a time where makers are being asked to connect directly to those roots and express that in our work.

■Kurata: When you say “root,” what do you mean by that?

■Yagi: The root is something like the essence of Kaikado that makes it what it is. I haven’t been able to articulate it either, it’s just a feeling that I have. When I place my work in front of my dad, there’s this shared sense that leads us to agree, “this one is good.” So the questions I have are, how can I convey that to other makers or pass it down to the next generation of artisans, and how can I communicate it to the people who use our tea caddies?

I’m able to share it today, by telling stories based on my experiences like I’m doing now, but nowadays we also have to reach those who can’t be part of a shared experience. That’s why I think it’ll become increasingly important to find ways of conveying the value that lies within the intuitive parts of our work.

■Kurata: I think we’ve come to a very nuanced point, so if the other speakers have any thoughts in response to that, please feel free to jump in.

■Kanaya: In both design and craft, I think the key concept is “deciding what not to do.” In my field of design, it’s surprisingly difficult to agree on the things we want to do, but it’s pretty easy to share what we want to avoid. For example, the decision not to outsource our production overseas has formed the foundation of our company.

I think it might be the same at Kaikado: they’ve been able to stay with selling one type of product because that has become Kaikado’s guiding concept behind the brand.

Seeing that picture of Kaikado from earlier, it made me realize that deciding what we should not do, allows us to see the flip side of the coin very clearly.

■Nakagawa: Right around this time three years ago, I participated in an exhibition in Milan. There, Yagi-san chose to show his tea caddy as a product they have continued making for 100 years that has not changed its form throughout their entire history. But I exhibited ki-oke of all different shapes. Why? Because my profession known as oke-ya (wooden bucket maker), is disappearing. When my grandfather was in training around 50 to 60 years ago, there were about 250 oke-ya shops in Kyoto city alone. But for a time, that number dropped to just three. Now we have four, after one of my former employees Taichi Kondo opened his own shop (Okeya Kondo).

■Yonehara: Mr. Kondo is in the audience, so we have two out of four here today!

■Nakagawa: In other words, oke-ya is a kind of critically endangered species. Under these circumstances, my choice has been to generate many mutations. Collaborating with designers is one example of cross-pollination to create new pieces. If I make a lot of those new forms, and even just one of them is able to adapt to the next environment, then oke-ya can continue to exist. I’m not sure about 1000 years from now, but I think we can aim to survive the next 100 years. This is why I make different forms in my work.

But I think even those new forms will eventually die out. Ultimately, it’s about diversity: we make different choices depending on our respective circumstance, practice, or business structure. There are different paths to choose from and we have to decide which is best for our own survival. I’ve been thinking a lot about the issue of continuation—how to preserve our field—and sustainability, especially in the context of “traditional craft.”

■Nagata: I’d like to add a few words to that. I think we have Mr. Hosoo (Masataka Hosoo / Hosoo Co., Ltd.) in the audience today. When I had the opportunity to speak with him at a talk event, I remember him sharing the equation “Craft = Technique multiplied by Material multiplied by Spirit.” For the makers, this might be true, but from my perspective, I think it’s missing the layers. That is to say, craft is the accumulation of complex forces that neither money nor a person can solve, like the layers of culture, civilization, and the natural environment.

I think that’s the main difference when you compare craft to other industries.

For example, I think even the people who make plastic bottles want to do something about the environment. I’m sure they are developing techniques and materials by trial and error to address the issue, but without the fundamental layers (of culture, etc.) it’s difficult to go any further. Seeing the recent resurgence of craft, and listening to everyone’s stories today, it confirmed my belief in the significance of these foundational layers.

■Kurata: I feel like Nagata-san has kindly moderated the talk for me, because our next topic is environmental issues. Would anyone like to share final comments before we move on?

■Yagi: A little while ago, Nakagawa-san created a new kind of ki-oke: a champagne cooler. This is something that started in his generation of the business. And apparently, the design is continuing to evolve. How does a creation from the present—like his champagne cooler—start to move towards the future and connect to the next generation? I think this process will give us insights into our work as we move forward. It should also offer hints on how to survive for industries that have sprung up in the past decade like the IT industry. Nakagawa-san, could you talk about your project in more detail?

■Nakagawa: I’ve kept this project under wraps, so I’d rather not make this too public, but we developed a champagne cooler in 2010, which became the official cooler of Dom Perignon. That gave us an opportunity for our name to be known.

Compared to the original cooler from 2010, the latest design has undergone significant upgrades. Currently, we’re at about version 8.5. Based on the initial feedback from customers and things I noticed while using it myself, I made a number of small adjustments. The appearance hasn’t changed very much, but I’ve modified the thickness of the wood and the structure.

At Nakagawa Mokkougei, we have slightly adjusted the measurements of our products over the years, even for things like the koshi-kake-dai (bath stool), which we’ve been making since my grandfather’s generation. Back then, the height measured about five sun, or 15 centimeters high. Then that became five sun five bu, six sun, and now it’s one shaku, or approximately 30 centimeters high (T/N: sun is a Japanese unit of measurement. There are ten bu in one sun and ten sun in one shaku). The height of the stool corresponds to the changes in the body size of Japanese people and bathtubs over time. As it shifted from Goemonburo-style tubs to “unit-baths,” the stools became taller. Although it’s a “traditional” craft, it never ceased to adapt to the changing times.

■Yagi: I realized that rather than looking back on the past from the present moment, he’s looking forward into the future as he makes his ki-oke. The champagne cooler is reflective of that.

I’m not suggesting that he is ignoring the past when he looks to the future, but I think his thinking on how to entrust the next generation with our creations, provides valuable insights.

Craft and Happiness

■Kurata: There’s no shortage of topics for conversation. I think what we just discussed was more about human creativity and ingenuity, trial and error, and the importance of continuing the work without pause. On the other hand, there’s also the issue of nature as it relates to craft. I think this is an unavoidable topic, which is why I’d like to bring it up as our final theme of discussion: “Craft and Happiness.” (Turning to Yonehara) I can’t really remember why we decided to include “happiness” in the title, but here we are.

■Yonehara: At this point, I can’t remember either. But I would just like this last part to dig deeper and broaden the conversation.

■Kurata: It’s extremely deep and we’ve only got 30 minutes left. Well, at least we made it this far.

■Yonehara: This topic might be too broad and open-ended but it’s a really important one.

■Kurata: An important topic indeed. We’ve talked a lot about people. Now, let’s talk about the parts that support the people. When we think about made-to-order products in the context of craft, I think there’s a dialogue not just with the customers but also with the materials. That’s one of the things I hope we can touch on, as we discuss our last topic from the perspective of nature. I’d like to have Yonehara-san start us off with the first story.

■Yonehara: I know we have to watch the time, so let me first share my point. Craft can only thrive in close proximity to nature, but most places have been urbanized in our modern era. With that in mind, I’d like you to look at this picture of yuzen-nagashi (the custom of washing dyed silks for kimono in the river).

This photo was taken around 1940. Yuzen-nagashi became an established practice in the Meiji period, and it reached its height between 1897 to 1906. People talk about this now nostalgically, but it was only about 100 years ago.

As was mentioned in part one of the discussion on fish skin, the dyeing industry increasingly shifted toward the use of chemical dyes once we entered the Meiji period. With that came an upsurge in the production of kyo-yuzen (Kyoto-style hand-painted silks) in Kyoto. In the process of making kyo-yuzen, you need to rinse off the excess paste and dye, and to do that efficiently, you need a constant flow of water. The most convenient place for that is a natural river. I think this photo is of the Katsura River, but they were doing this in Kamo River as well. In fact, most rivers running through Kyoto city at the time were probably used for yuzen-nagashi, and dyers would compete for spots in the upstream areas.

Yuzen-nagashi became popular around 1897, and after about 50 years, discussions arose regarding its negative impact on the environment. Eventually, during the late 1960s and early 70s, the practice was banned as more and more regulations and laws were put into place to protect the environment from industrial waste. It was around this time that the use of noborigama (the climbing kiln) in Kyoto city was also banned.

But you can’t do away with the process of yuzen-nagashi just because it becomes prohibited. So the dyers in Kyoto built artificial rivers inside their workshops to rinse out their silks. While they can’t change the process itself, the industry found a way to respond to societal concerns.

In the field of craft, it seems inevitable that we unintentionally harm the environment. I think there’s been significant impact on nature, especially during times when there have been efforts to revitalize and promote craft.

Something I want to ask Nakagawa-san, is his thoughts on natural and man-made forests. I personally wish more people had a nuanced understanding of how man-made forests function. Trees in forested mountains don’t just naturally grow on their own before they are harvested. There are stewards who look after the trees and woodcutters who carefully harvest them and distributors who transport the lumber to the artisans’ workshops. I want to reexamine this process leading up to a wooden object being made.

This could be called the “upstream sector” of craft, concerning the procurement of materials. I want to explore, with as many people as possible, ways of building a relationship with the invisible force of nature.

■Kurata: Listening to your point now reminded me of something I heard when I participated in a symposium with the dyer Fukumi Shimura about ten years ago.

She said something that startled me, which was, “creation is contamination.” That is to say, nature is already beautiful as it is, so for humans to intervene in it is to disturb and pollute it. She was saying you can’t make something truly beautiful unless you are aware of that. I was both shocked and moved that this was coming from someone who works not with chemicals but with plant dyes, and yet she was calling her own life’s work “an act of pollution.”

But maybe she felt this way because she worked so closely with nature. I don’t think you would come to this realization unless you were seeing firsthand, how your work was contaminating your surroundings. In this way, I think there’s a part of craft that is constantly interfacing with nature. I’d like to have Nakagawa-san open our next discussion on “Artisans’ Work and Nature.”

Artisans’ Work and Nature

■Nakagawa: Regarding the wood used in craft, there is a concept called ten-nen-bi (literally “natural beauty”). There are natural forests and plantation forests, and timber harvested from both. This is something that has been in discussion for a long time in woodworking.

In the romanticized narrative of craft and manufacturing, I think there is a common perception that natural timber is better than plantation timber or that a table made of natural wood is the best. But natural wood takes several hundred to several thousand years to mature. In reality, there are very few natural forests left in Japan, because they have all been developed. Looking back in history, up until the Yayoi period (which ended around 300 AD) there were many cedar forests with trees over 2,000 years old that were 5 meters in diameter. That’s why it was possible to build the 50-meter tall structure of the original Izumo Taisha shrine. This was believed to be a legend until recent discoveries proved that at the time, there were still trees that were over 2,000 years old. Since then, humans have continued logging over the course of history and now we live in a time where a 300-year-old tree is considered “ancient.” We have drastically changed the natural environment. But trees are still very important to us and ones that are several hundred years old are highly prized.

Going back to what I said in the previous discussion about the art world, if “uniqueness” is valued in Art, it’s necessary to value inter-generational sustainability in Craft.

What I mean to say is, the trees in man-made forests have been planted and cared for over three, four generations of foresters, who have passed down stewardship from parent to child. It looks just like natural timber, but there is a lot of human involvement in its growth.

Under a national policy, especially after the war (World War II), reforestation efforts advanced significantly in Japan. The cedar trees planted during that time now causes hay fever, but the wood from that era is of excellent quality. Those efforts have resulted in high-quality timber that are about 80-90 years old. I think there is a need to move away from this over-glorification of natural wood and we can start by deliberately choosing to work with plantation wood.

I look for wood from Shiga prefecture where my studio is based, or from Kyoto. Unlike the previous generation of makers who sought after precious wood from all around the country, I feel that our generation has the responsibility to purchase timber from foresters that have properly stewarded the mountains across multiple generations.

■Nagata: Your point brought to mind the fact that the word kougei (craft) was first used in Japan during the Meiji period. That was when the act of making things, which was previously known as hyakkou became roughly categorized as kougei. The origin of this word can be traced to the 2,000-year-old Chinese text called Kaogong ji (Book of Diverse Crafts). In it, craft is divided into the four elements of heaven, earth, materials, and skill, and it states that good craft can be made only when the climate, regional characteristics, material beauty, and human knowledge fit together perfectly. In that sense, the word kougei refers to the act of gathering the finest materials and elements—some of which we can control and others we cannot—and making something out of it. When the Japanese government brought the word into use in the Meiji period, perhaps they imbued it with the idea of combining human knowledge with something we do not have power over: nature. Maybe, the word kougei itself started out as a concept to integrate our skills and knowledge with nature.

■Kurata: I’m afraid this is going to make our conversation quite abstract, but I was reminded of something that I want to share. When the late architect Kazuhiro Kojima published his collection of works about ten years ago, he said that 21st-century architecture could be described as “cultivation.” The architecture up until that point, to put it simply, consisted of someone drawing plans for a building and plopping it down on a piece of land. It didn’t take into account any kind of social context, much less the natural environment. It was a project with pre-determined goals, forcibly inserted into the designated location. According to Kojima, that was the standard format of an architecture project. But from now into the future, the regional variables like the land or the community will constantly change. We have to build or implement the plan in line with those changes, as though we are farmers cultivating the land and growing crops. I think that’s what Kojima-san meant when he said that. As I listened to Nagata-san talk about the original meaning hidden in the word kougei, I saw the connection to human activities like agriculture. Sorry this is very metaphorical.

■Nakagawa: There are any number of problems, but I think it all comes down to how humans interact with nature. The issue of satoyama is one that is often brought up. (T/N: literally “village mountain,” satoyama refers to the area between the deep mountains and the village and is considered representative of human coexistence with nature). Compared to natural forests and old-growth forests, satoyama makes up most of Japan’s mountains. Now the problem is that the ecosystem in the satoyama is out of balance. I personally believe that Japanese people originally knew how to interact with nature, but now, something is off. We need to reset the course, and I think craft can play a useful role in that.

The Japanese and European views of nature are totally different. In Japan, views on nature are premised on human involvement. For example, the traditional Japanese home with a thatched roof won’t even last ten years if there is no one living in it. They last 200 or 300 years because the residents clean the house and open the windows to let the fresh air in. It’s the same with kyo-machiya (traditional Kyoto-style townhouse). Europe’s view of nature insists on the absence of humans. It’s the worldview of a culture of stone construction. A material that will stay the same over hundreds of years and does not change, regardless of human presence.

It came up earlier when we were talking about buildings, that Japanese architecture “permits” human intervention, or to put it another way, it encompasses the changes in variables that we talked about.

■Kurata: It feels we are starting to wrap up this section. A discussion is like a living organism sometimes. I know there’s probably more to say on this, but we have one last theme that we prepared so I’d like to move on to that before we take a look back on this session.

From “I” to “We”

■Yagi: When I’ve talked with Nakagawa-san in the past, we came to this idea that making things is not solely for the self (‘I’) but for the collective ‘we.’

Thinking about this again now, I don’t think it’s just craft or manufacturing that should take this collective stance, but also our relationships with our surroundings, and to one another. There are movements overseas like the national trust, where citizens can acquire forest land to be conserved. On the other hand, in modern-day Japan, there continues to be human intervention in forests, which means there are labor costs associated with the preservation of nature. I think Craft has a role to play in connecting people to nature, and to each other, which is another reason why the idea of ‘we’ is important for us.

At the same time, in the context of craft, “we” doesn’t just refer to the general public. I think there’s actually a tiny “i” in “WE.” Not a capital “I” but a small self, one the size of an ‘i’ that might fit between the “W” and “E” to make a “WiE.” You live your whole life thinking about that small “i” and when it starts to fade away, that’s when you pass the baton to the next generation. As I was thinking about all of this, I felt that the commonality amongst Japanese people is that we live our lives in relation to kougei. Perhaps this is something I can pass on to future generations.

■Kurata: This is a slight digression, but in the Japanese view of nature, there is a concept known as uotsukirin (“fish-breeding forest”), a forest with fish attached to it, or the view that there are fish in the forest. You might think, “how could there be fish in a forest?” but this expresses the idea that protecting the forest will enrich the fishing areas at the outlet of the drainage basin. The thinking goes that you’re not just protecting what’s immediately in front of you, you’re also enriching the resources that is valuable to someone far away.

Much like uotsukirin, the idea of “we” also contains an awareness of the link between the forest and the sea. We can’t just look at the ocean if we want to fish, we also have to steward the land.

This word is also a way to say that “I” does not stay isolated inside itself, closed off from the rest of the world. It’s connected to a larger “we.” Now that we’ve come this far, it’s time to connect this idea to craft. I think it offers us hints to thinking about the relationship between craft and nature. What do you think?

■Yonehara: In response to Nakagawa-san’s comment earlier about satoyama, I’d like to share a recent move towards increasing domestic production of urushi (natural lacquer). There are efforts to replant lacquer trees in regions that used to be known for it and grow them over ten to fifteen years to harvest the sap and make lacquer. All across the country there are movements to revive urushi production, which, for most of these areas, has been lost for 50 years. Tamba is a well-known region in Kyoto prefecture for urushi.

What’s different from the old days is that residential areas have increasingly encroached on satoyama. Even in places where people used to plant lacquer trees, the neighboring residents now are opposed to replanting because it causes rashes (T/N: lacquer trees contain urushiol, an oil also found in plants like poison ivy and poison oak which can cause rashes upon contact). The people who want to plant lacquer trees see them as symbolizing the memories of the land or the industry, but they face opposition from their own community. I thought that this should be a part of our discussion about “we.”

Whether you disagree with the replanting efforts or not, it wouldn’t be an issue if everyone took the responsibility to engage in a conversation about these initiatives. But unfortunately, the debates tend to go unresolved. What often ends up happening is that the project gives up on tree-planting due to the opposing voices.

One consequence of planting only in areas permitted by local residents, is that lacquer trees are now scattered across the mountains. In urushi-kaki (the process of tapping urushi trees) you only get about one milk bottle worth of sap from a tree. Because the yield is so small, it’s more efficient if the urushi-kaki artisans can do their day’s work within a smaller radius, so they don’t have to move around any more than they have to. They already hike quite a distance around the mountain, going from tree to tree. But in reality, they can only collect a little for each area of growth, before they have to get on their mini-trucks and drive to the next mountain to continue collecting.

While there’s been a rise in the promotion and encouragement of craft and regional development, we are also seeing issues like this on-site. At the root of this problem are the emotions of many people, so you can only solve it through communication. It’s not so straightforward, either. No one is at fault, but we do need to put in a little more effort to talk to each other. Asserting one’s interests won’t solve the problem. It’s a difficult issue.

■Yagi: I agree that it’s crucial to look at the problems around the environment for making. In metalcraft for example, our work (making tea caddies) produces some noise but something like tankin (metal hammering) can be really loud. You can’t set up your workshop inside your home anymore. That means we have to find a place to work that isn’t as densely populated, which in turn leads to a world where craft is no longer part of the everyday landscape. Perhaps this is one reason behind what Nagata-san was describing earlier, where we don’t see tatami being made in our neighborhoods anymore.

The fact that makers themselves have to make appearances in the media or places like this (symposiums) to share “the meaning and value of craft,” points to the extent to which Craft has become disconnected from the rest of society.

I don’t have any answers, but I’m now trying to travel more overseas, visiting one city at a time to convey the value of craft through organizing opportunities to experience it. We need to create spaces to share with our customers the true value of what we make. I think we’ve come to a moment when all of us, including the makers, distributors and everyone in between, have to think very seriously about this.

In a book I read the other day, it said “buy craft to keep craft alive.” But the truth is, in the past, craft products did not sell because we did nothing to try and communicate their essence. That’s why, for the future of craft, I hope we can all think about what makes craft worth buying.

■Kanaya: What I see as a challenge for the manufacturing and craft industries all around the country is that there are no tonya (wholesalers) who work closely with the artisans like they used to. In the past, the wholesalers were the ones who put together sales plans and were in charge of distribution routes, which meant that there could be a relationship between merchants and artisans. The roles were divided, and therefore the artisans were able to focus solely on their craft. But now, every production region is in a situation where the artisans have to go out and sell their products themselves. Under the current condition, some makers are finding it difficult to continue handling the business into the future, and they are choosing to leave the industry.

The problem is that we didn’t update our systems and structures in the past. I think this can be said of both the business and the craft. It may be a strange way to put it, but it’s as if the bill came due and the current generation has to deal with the heavy question of “what do we do now?” With the current state of things, I don’t think it’s ok to just leave everything to our sons and daughters and wish them luck.

I travel all over the country, and I see this same problem everywhere. There are no systems in place to strengthen the production region, and as Yagi-san pointed out, there are not enough allies. We are seeing more and more makers, but there isn’t a rise in communicators like Nagata-san or myself who make the connections. I think there’s a set number of us, but I don’t get the impression that the number is increasing in any significant way.

■Nagata: I would say the people in our scene haven’t changed for the past ten years or so.

■Kanaya: Exactly. It’s always the same faces, even in the magazines. Because there’s more media coverage of craft, it seems like there are more of us, but if you look closer it’s all the familiar names. And that worries me. People from Tokyo will ‘parachute’ into rural areas to help out, and when the money runs out, they leave. No matter how many times you repeat this process, this is not the way to revitalize a region.

Just the other day, we received an inquiry from a credit union with a similar short-term proposal. If we don’t support the growth of local wholesalers who can oversee and manage the industry in the region, the makers will end up becoming isolated after the program ends. To avoid this, we need to cultivate the necessary actors within the community.

I think most of the people here today are feeling the same thing. I’m sure some people are doing well even in this current situation, but it still worries me that we’re not seeing an increase in the number of wholesale traders.

■Kurata: Considering the time, I think we better invite Nakamura-san to the table for the final discussion. I can tell that he’s itching to join us, his expression says, “hurry up and call my name already!” (laughs)

We are preparing for the final part of the symposium now, but there is still a full hour left. Is everyone doing ok? Does anyone have questions about something that was discussed or have topics you’d like us to delve into a little more?

■Sacko: (from the audience) I have a question.

■Kurata: Yes, Sacko-san.

■Sacko: I’d like to comment on the discussion about the word “we.” In English, it signifies a cluster of individuals, so it’s a little different from the sense of locality or community that people often refer to in Japan. When written in English, I feel that “we” points more to the individual participating in a group, or the role of the individual within a group, or even individual profit.

It’s a little different from the Japanese notion of ‘joining hands without profit motives,’ as in the context of traditional industries. It seems that the discussion focused too heavily on the individual and the topics that each speaker presented, and to me, that’s where the problem lies. You don’t have to force the conversation to fit the word “we,” I think there’s a different, more suitable expression out there.

I think some words just can’t be fully translated. Trying to impose a definition onto a word can render it meaningless. Essentially the word should convey the sense of collectivism in Japan but it doesn’t come through in the word “we.”

■Yagi: We put a lot of thought into the word choice but to tell you the truth, we couldn’t find the perfect word for it in English. I was also considering lining up four “I”s as an alternative.

I first tried using the word “we” when I was in Canada recently, not in the native context of the word, but as a word in the shared language that could be understood by an English-speaking audience, even though it wasn’t 100% accurate. I would appreciate it if anyone has a suggestion for another word we could use.

■Kurata: I was quite critical of the theme during the meeting we had beforehand. It wasn’t so much about the definition, I personally thought we should use a Japanese word instead, considering the fact that Japanese terms have become more frequently used overseas in recent years, even in Europe. There’s a depth to the meaning of Japanese words, so why not just write it out in English letters? For example, people often use the word “zen,” even if incorrectly. Rather than trying to come up with a translation, you could allow the original word and meaning to expand its reach. I think it’s better to use the words we have in the lexicon of Japanese craft as they are, and try to spread the meaning.

■Nakagawa: For me, I think it’s a little risky to use the word kougei abroad without translating it. There is a move to do so in some parts of the field, and I think it’s problematic. But I also recognize that the words kougei and shokunin are not the same as “craft” and “artisan.” It’s a challenge to figure out how to convey the subtle difference in nuance.

■Kurata: I’d like to say one more thing, which is that the table we have today embodies the spirit of “we.” The designer gave his all to make this “we table” just for this occasion.

■Yonehara: We asked TSUGI, a design firm based in Sabae City, Fukui Prefecture, and Toshiro Mori, a product designer also based in Sabae City, to create a table for our discussion that is a physical representation of today’s theme.

He chose to use plastic, even though sustainability is one of the major points of discussion today. He chose a material that is often excluded in such conversations, in hopes to show that some of the concerns can be overcome through the power of design.