We–The Future Seen Through Craft

Inaugural symposium hosted by the Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries at Kyoto Seika University and Kyoto Kougei Week 2019

Date and Time: 1 September 2019 13:00-17:30 (Doors Open 12:00 noon)

Venue: Kyoto International Manga Museum 1F Multipurpose Video Hall

Karasuma-Oike, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto 604-0846 JAPAN (former Tatsuike Primary School)

Host: Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries, Kyoto Seika University

Support: Kyoto Kougei Week Executive Committee

Cooperation: Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan; Kyoto Prefecture; Kyoto City; Kyoto Chamber of Commerce and Industry

Participation: Free / Pre-registration required

We - The Future Seen Through Craft: On the Publication of the Full Transcript

We - The Future Seen Through Craft: Opening Remarks

We - The Future Seen Through Craft【Part One】Fish Skin as a Fashion Material and the Dyeing Techniques of Kyoto

We - The Future Seen Through Craft【Part Two】For the Next 1000 Years of Handcrafts

We - The Future Seen Through Craft【Discussion】Passing the Baton to the Future

[In Pictures] We - The Future Seen Through Craft

We–The Future Seen Through Craft:

【Part One】Fish Skin as a Fashion Material and the Dyeing Techniques of Kyoto

Panelists

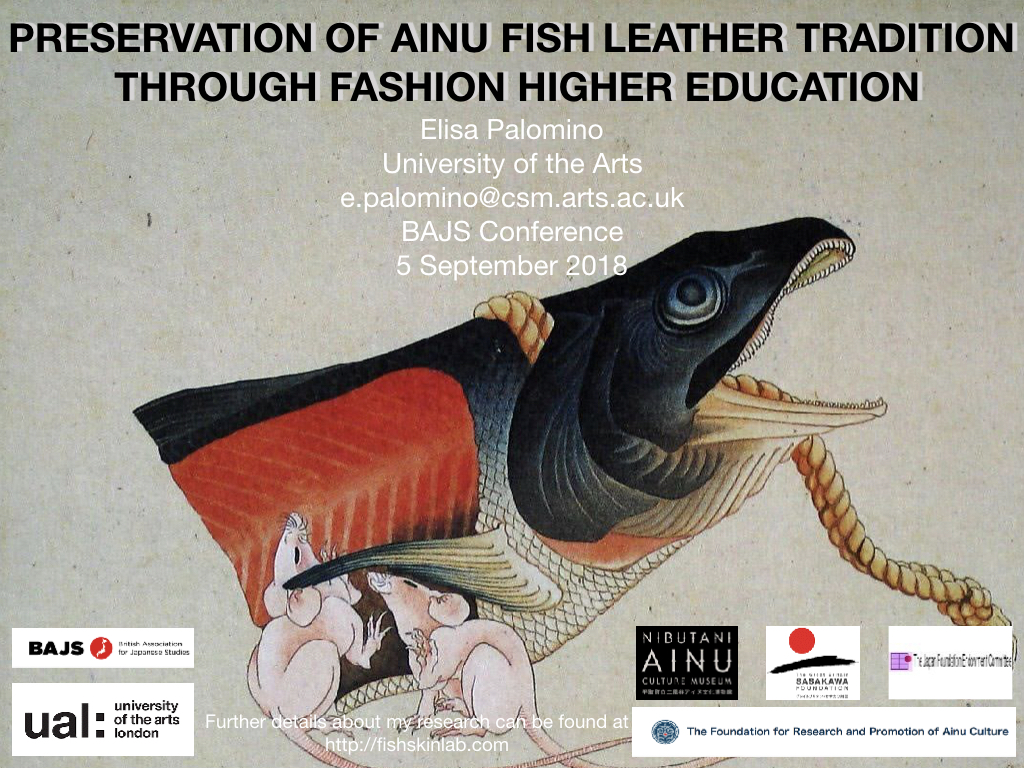

Elisa Palomino (Pathway Leader, BA Fashion Print, Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London)

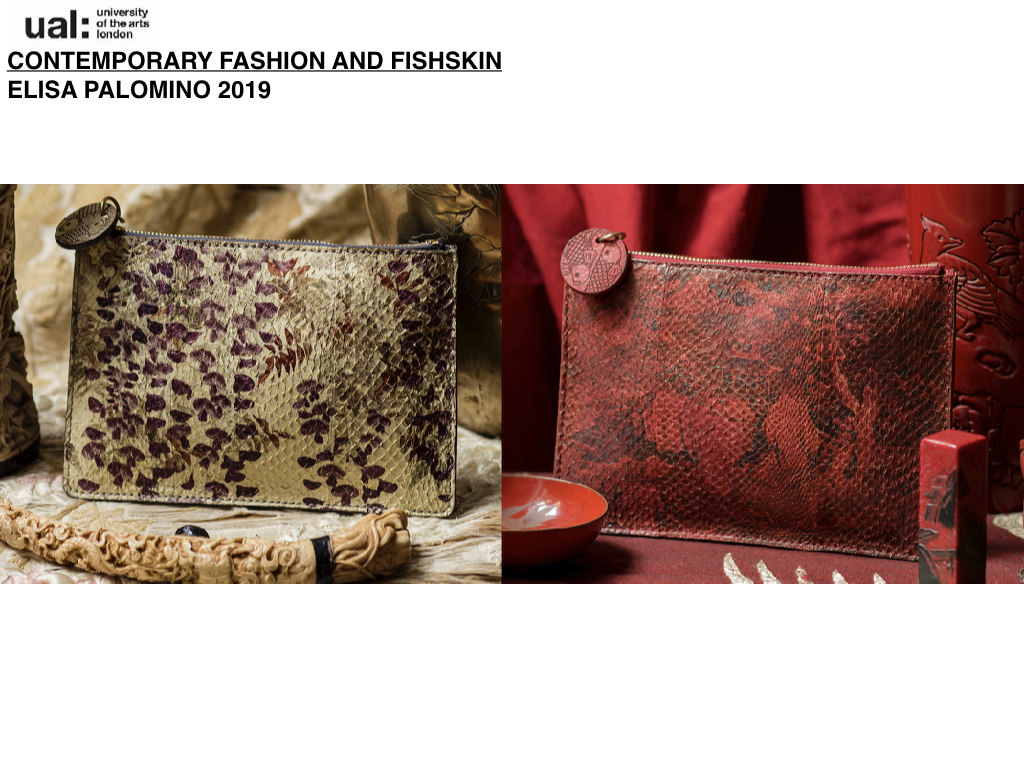

Elisa Palomino is a recognized fashion designer with over 25 years’ experience working in the fashion luxury industry, academia, museums and galleries. Her training has been working at brands such John Galliano, Christian Dior, Roberto Cavalli, Moschino and Diane von Furstenberg. In 2010 she launched her label showing at New York, Milan, Rome, Madrid and London fashion weeks. Since 2012 she directs the BA Fashion Print department at Central San Martins and is member of the Textile Future Research Centre TFRC. Elisa has pioneered the adoption of sustainable practices into the Fashion education curriculum.

Elisa’s research focus is inter-disciplinary, within the context of sustainability, integrating traditional craftsmanship methods with new technologies, keeping in mind the importance of environmental, ethical, and social impact of fashion materials. Her research aims to activate new models for sustainable textiles encouraging indigenous artisans to continue to produce craft and to pass their skills onto others, particularly within their own communities, creating socially engaging and participative art projects. She is a recipient of several academic scholarships: Fulbright Scholar Award: ‘Arctic Fishskin clothing traditions’ at the Smithsonian Institute, AHRC LDoc scholarship, Daiwa Foundation, The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.

--

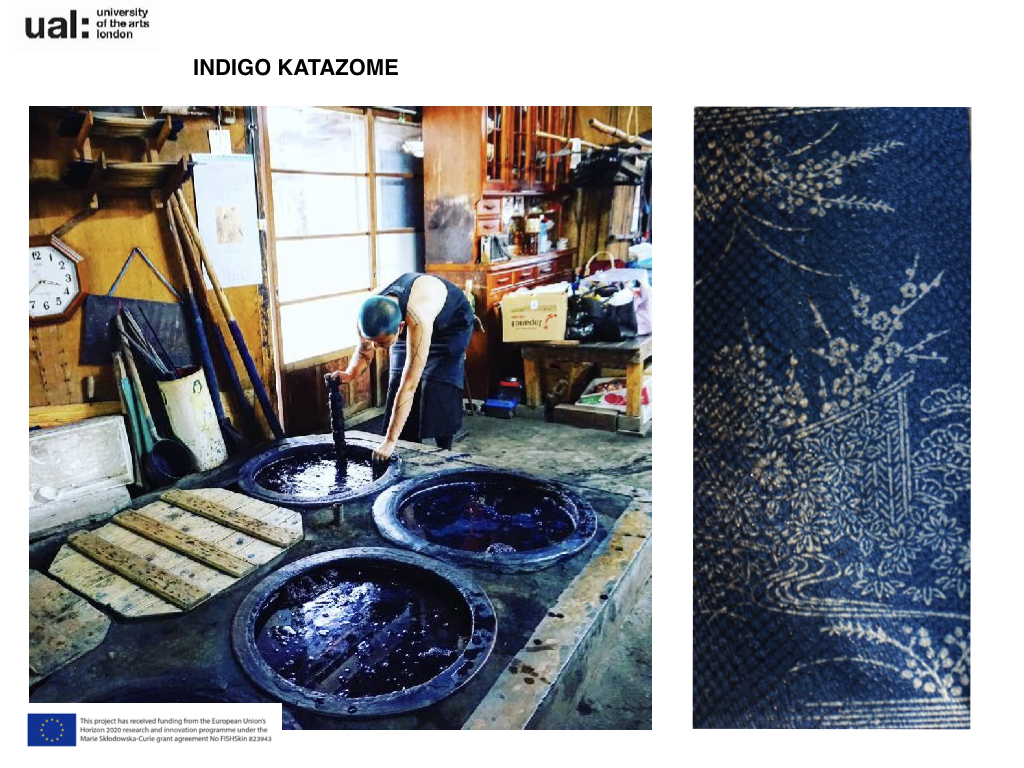

Issei Matsuyama (Matsuyama Senko)

Born 1978 in Kyoto. After graduating from an arts university, Matsuyama joined the family business, Matsuyama Senko, where he apprenticed under his father. The company specializes in a traditional dyeing technique known as shinzen (dip-dyeing), and primarily dyes Buddhist monastic robes and kimonos. Matsuyama Senko's highly refined techniques and modern sensibilities have garnered high acclaim. Matsuyama is a current member and former president (2009-2010) of the Kyoto Traditional Industry Wakaba Association, which aims to develop and support the continuation of Kyoto’s traditional industries. In 2015, he was recognized as a "Future Master Artisan" by Kyoto City. In the fish skin project, he dyes fish leather using plant-based dyes.

Mitsuhiro Kokita (Professor, Kyoto Seika University Faculty of Popular Culture Fashion Course)

Born in 1975. Kokita holds a BA in Fashion/Womenswear and an MA in Fashion/Menswear from Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design. Prior to his current position, he worked for a major fashion brand and an apparel company, designed for the prêt-à-porter line of a long-established tailor, and ran his own brand while teaching at other universities. Kokita is a member of the Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries at Kyoto Seika University.

--

Moderator

Yuji Yonehara (Director, Kyoto Seika University Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries)

Born 1977 in Kyoto Prefecture. Yonehara is a Kyoto-based writer and journalist specializing in the field of craft. In 2017, he was appointed Special Lecturer at Kyoto Seika University’s Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries. His work focuses on social research and education in the context of craft. Publications include Kyoto Shokunin - Takumi no Tenohira “Kyoto Artisans: The Palms of the Masters,” Kyoto Shinise - Noren no Kokoro “Historic Kyoto Stores - The Spirit of Noren” (co-author, Suiyosha), Listen to the Blues of Artisan in Kyoto (Keihanshin L Magazine), and The Emperor Higashiyama's Enthronement Ceremony in the Edo Period, and Its 1/4 Size Model (co-author, Seigensha).

Note:

The Japanese honorific "-san" is used throughout the text in place of Mr./Ms.

//////////////////////////////////

Some of you may be wondering what this session is about, having read the title in the program. This first part will focus on fish skin and fish leather. It’s about fashion but it’s also about kougei (“craft” - see note below). I would first like to give a brief overview of the fish skin project.

Amidst these concerns in the fashion world, a research project began. Gathering the resources of nine international institutions including Kyoto Seika University, the project aims to develop the techniques of tanning, dyeing, and sewing the skin of salmon and other fish caught in Iceland to produce a possible alternative to exotic leather.

Kyoto Seika University has been conducting experiments to dye fish skin together with textile dyers in Kyoto. Bearing in mind the issues of sustainability and the natural environment that inspired this research in the first place, we’ve created samples using natural dyes and hand-dyeing techniques. Later in this session, I will ask Matsuyama-san, the textile dyer who has worked on those tests, to talk about the technical aspects of the process.

But first, we will hear from the research leader, Elisa-san. She will give a presentation on the project outline and share some details of the research.

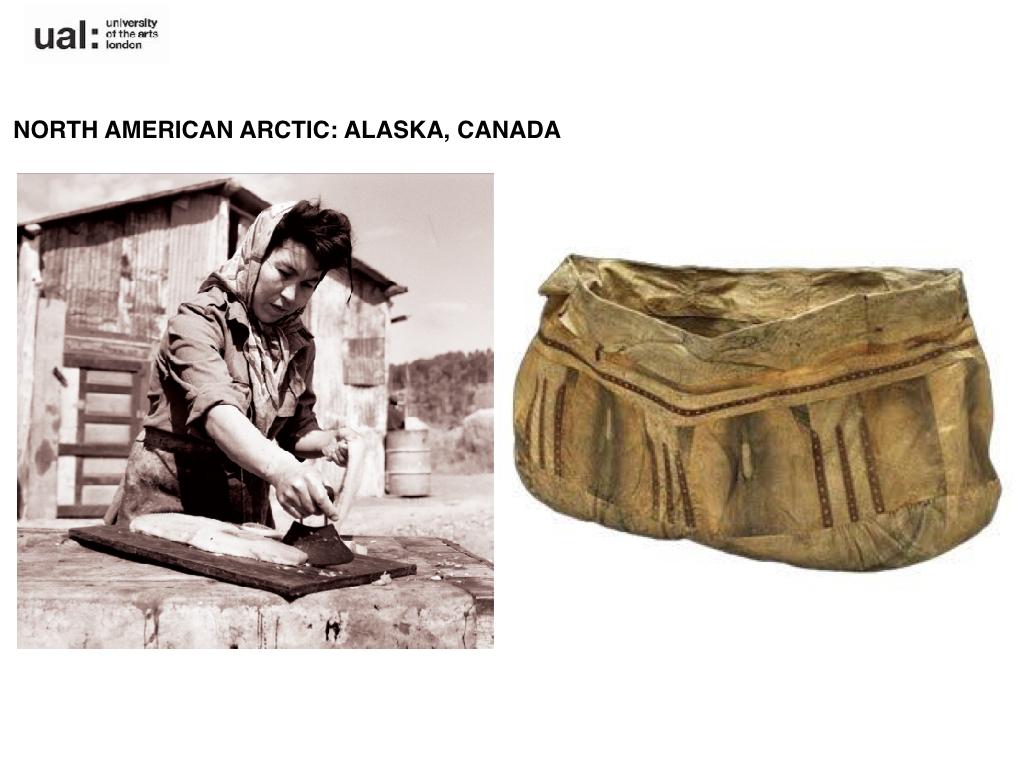

I just came directly from Alaska and Washington D.C. where I was working at the Smithsonian Institution with funding from a Fulbright award to develop the fish skin project with different Alaskan Native people who have been working with fish skin for generations.

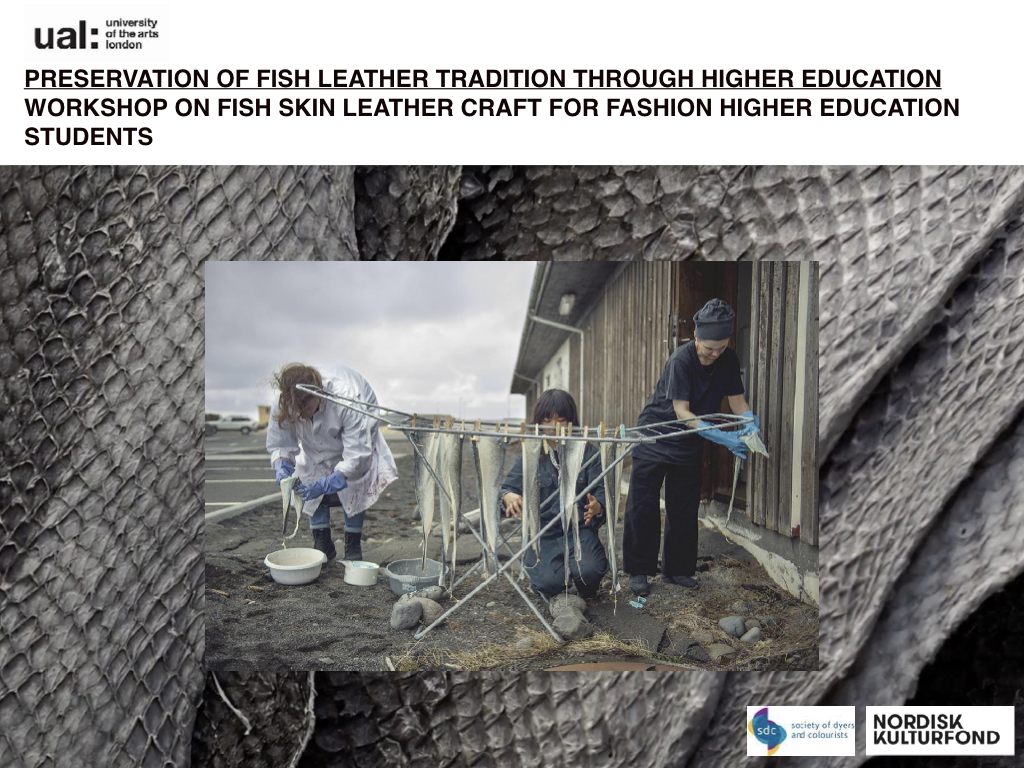

I have also been involved in the fish skin Horizon 2020 European project that we will be discussing later on. There are other projects like the Worth partnership, which is another European project. I have been hosting workshops with different universities all around the world, connecting indigenous people with fashion students in higher education. The European project that Kyoto Seika University is involved in aims to develop fish skin as sustainable raw material for the fashion industry.

The really important thing about this project is that it combines the academy and industry. I believe we have to bring both strengths together: what the academy has to offer as well as the fashion industry. There are a lot of problems lately within the fashion industry in regard to sustainability. So, the fashion industry is looking into new raw materials, which are more sustainable, and this is how our project fits into the bigger picture.

We are also trying to look into sustainable production of the material, which is already happening right now at Atlantic Leather. They are working now with local communities of fisheries in Iceland and are bringing new jobs to coastal dwellers.

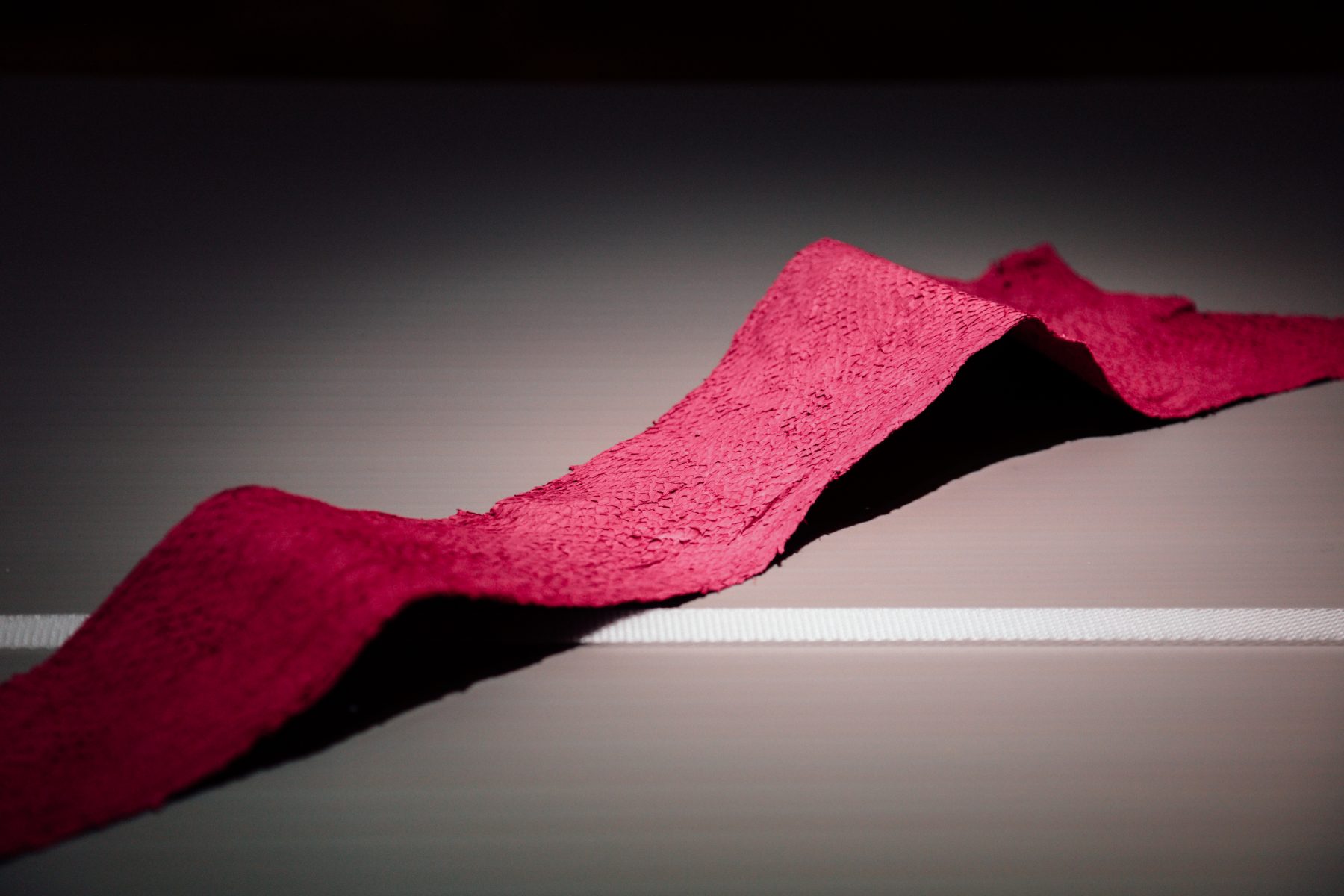

The eco-innovation that the project has brought into the fashion industry includes developing chrome-free tanning, natural dyes, and water-based digital prints. With these processes, fish skin can definitely become an alternative to exotic leathers like crocodile or snakes.

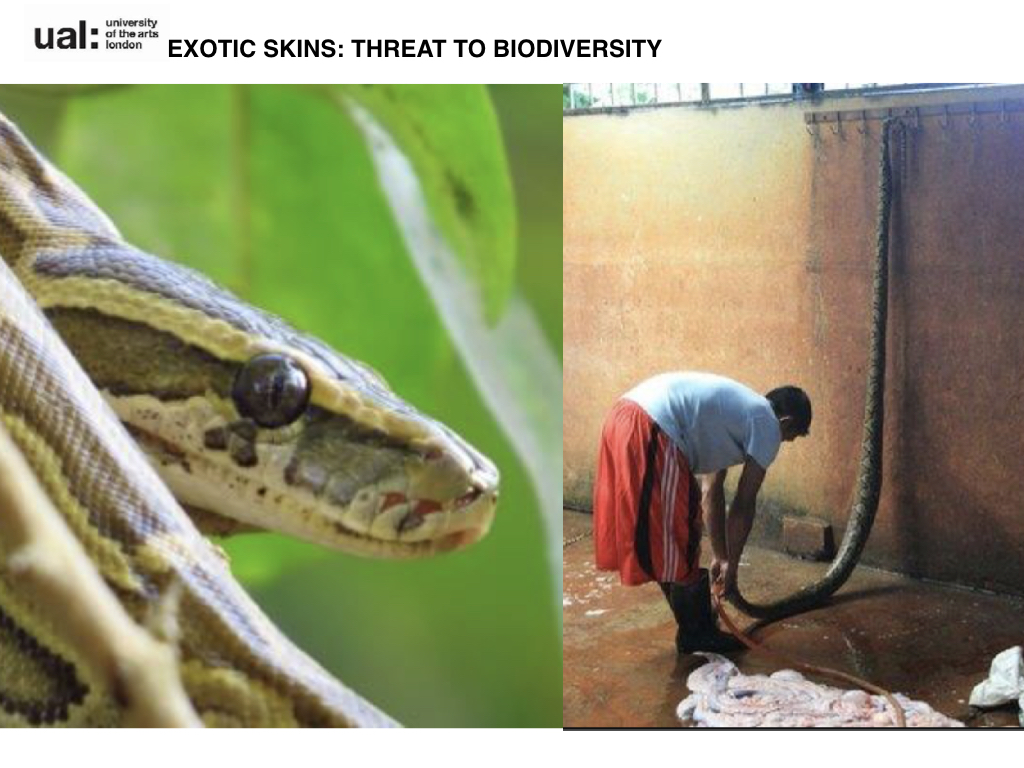

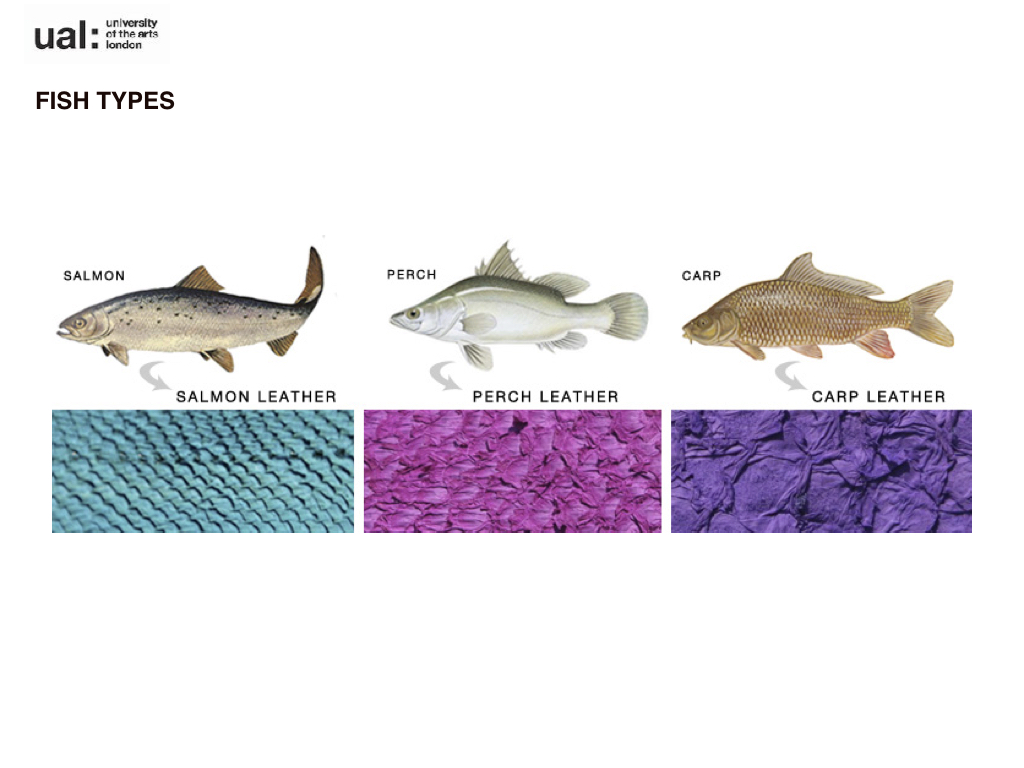

If we look at exotic leather and compare it with fish leather, there are quite a lot of differences between the two. For instance, fish leather is a byproduct of the food industry. Fish leather only uses non-endangered species like salmon, perch, wolfish, while exotic leather uses snakes and crocodiles that are farmed solely for the skins.

Fish leather is produced with geothermal energy from the Icelandic volcanoes, and uses vegetable tanning developed by Atlantic Leather, in contrast to the chrome tanned exotic leather. There are other advantages of fish skin, like its strength, which comes from the crosshatch fibers of the fish.

Furthermore, the way workers are treated in different companies is very different. In Vietnam, where most of the exotic leathers are produced, there is an unfair treatment of the workers who receive very low wages. But there is a huge profit by the luxury industry who eventually sells these leather products. This is not the case for fish leather and the people working in Atlantic Leather.

There is also all the inhumane treatment of animals. Sometimes up to 220 crocodiles are crammed in every pool, waiting to be slaughtered. Snakes are forcibly pumped with water while it’s alive to obtain a larger surface area for the production of snakeskin.

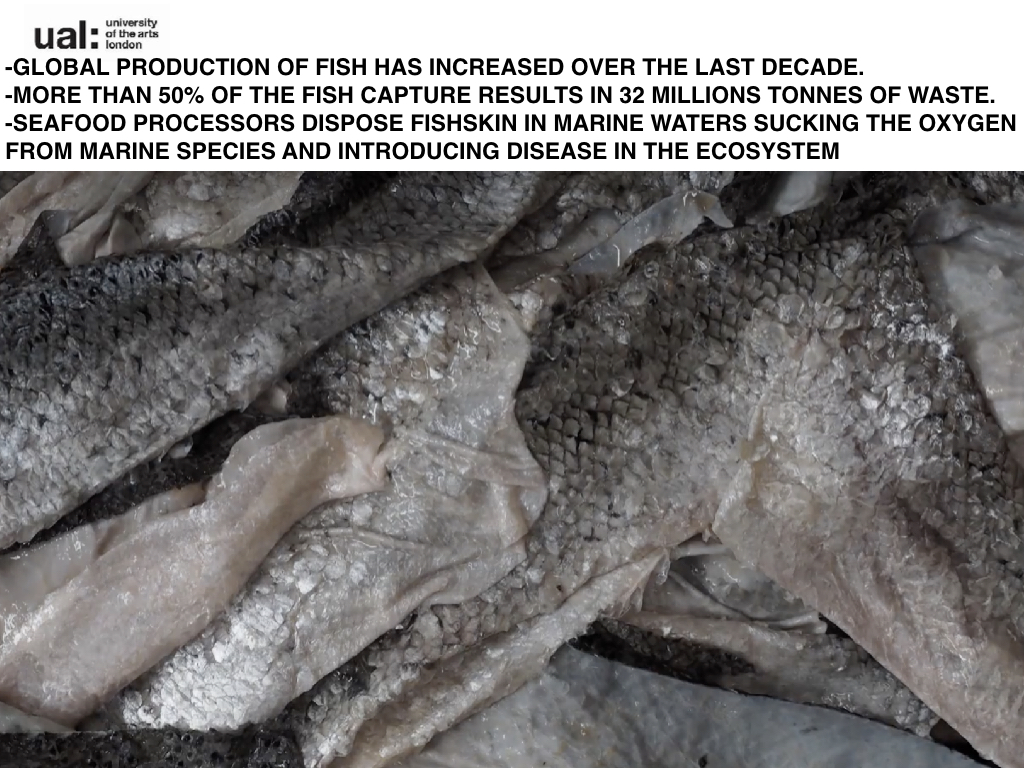

Our society is going through a lot of changes, including the way we eat. Because there are a lot of people who have stopped eating meat, there is a much bigger consumption of fish. There are also health benefits from eating fish, such as omega-3, and so on. This means that the global production has increased, but at the same time, more than 50% of the fish capture results in 32 million tons of waste.

One of our main partners is Atlantic Leather, which is the largest fish skin tannery in the world. They have been producing fish skin since 1994 and it has taken them more than 10 years to arrive at the best process of tanning fish skin because it is not the same as other leathers like cowhides. You have to work with different temperatures. If the temperature is too high, it will melt and you end up with fish soup instead of fish leather.

Another important fact about Atlantic Leather is that they are looking into the history of Iceland. Fisheries has been the most important industry for the country since the ninth century.

They also have responsible production practices. For example, they only use sustainably managed, farmed fish from the Nordic region; no wild salmon is used for the skins.

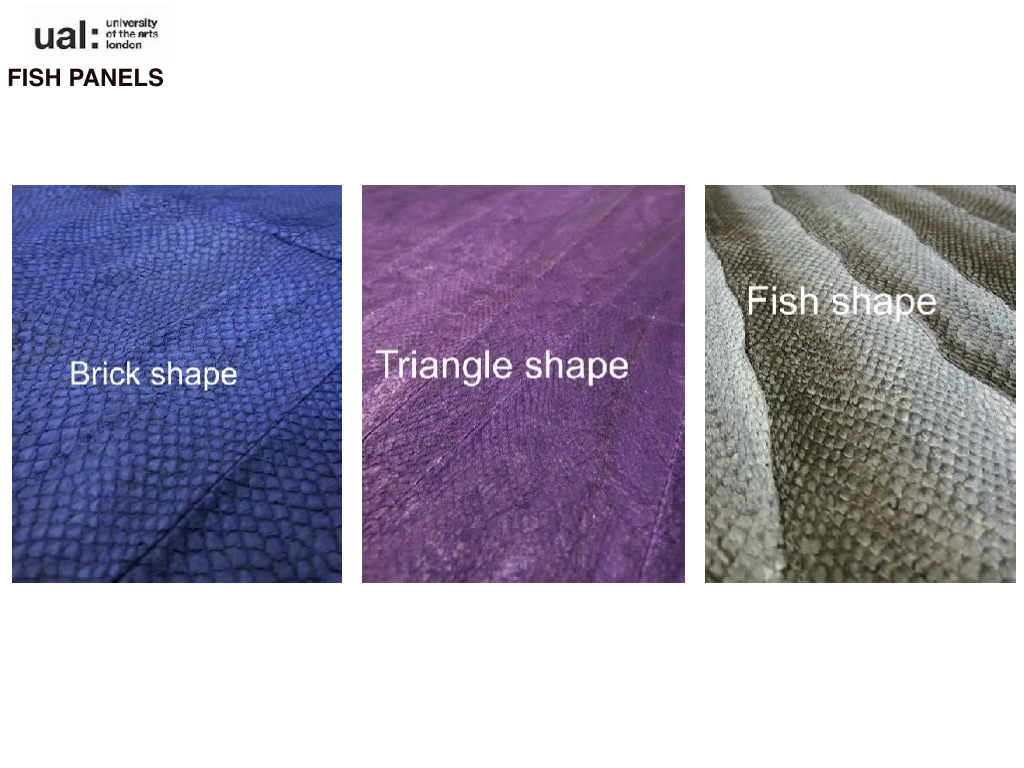

These (in the photo) are some of the panels that they sell, because the problem with fish skin is that it is very narrow. In order to make panels that can be used in fashion and not just for accessories, they provide different kinds of panels stitched together in brick shapes, triangle shapes and fish shapes. They also have ways of working with fish skin to create a patent leather like effect or a holographic mirror effect with foil.

What we have been able to introduce to the project is the practice of vegetable tanning, which uses different trees for different effects, such as the bark of the mimosa tree. Now the material has become a big success in major fabric fairs like Première Vision.

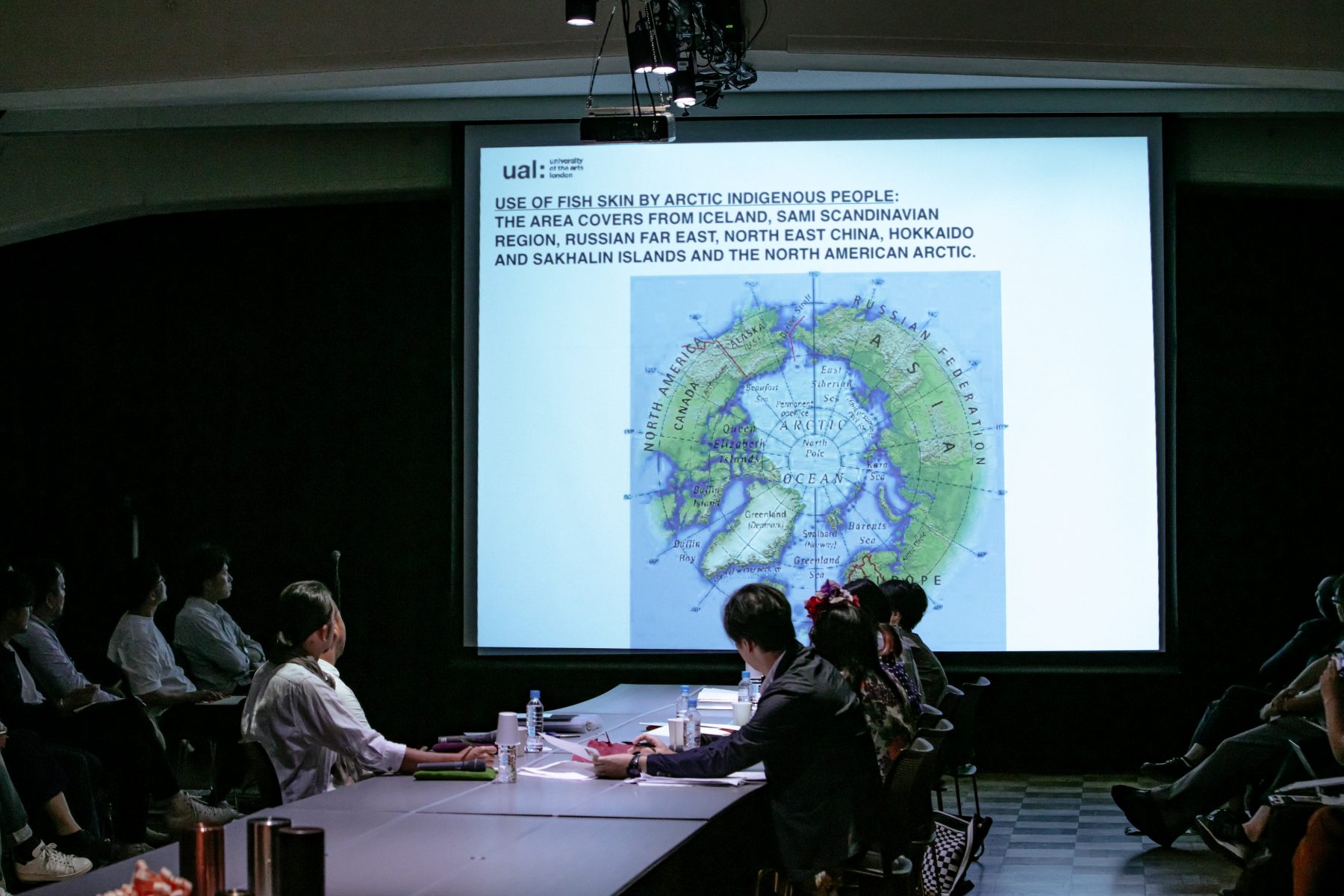

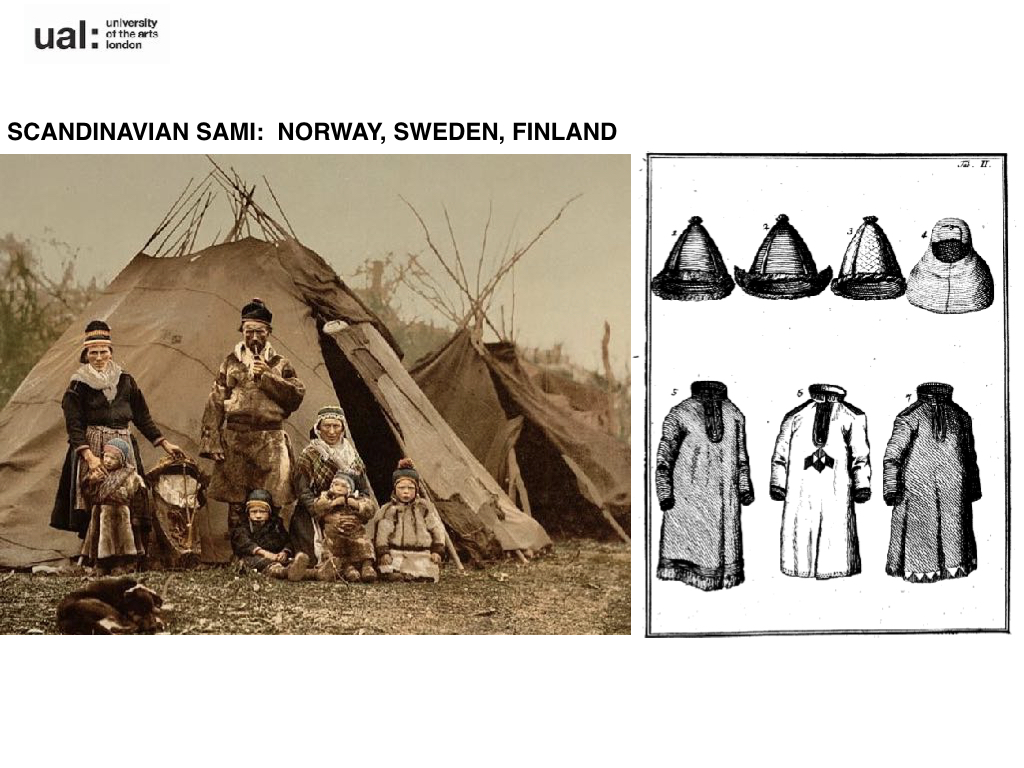

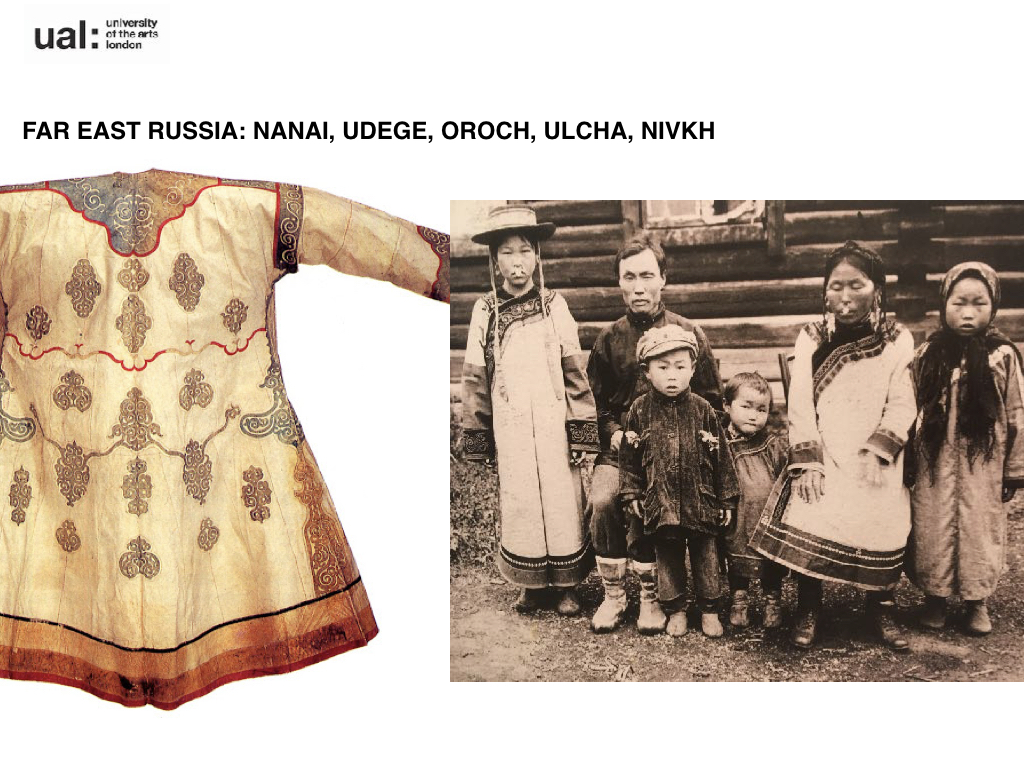

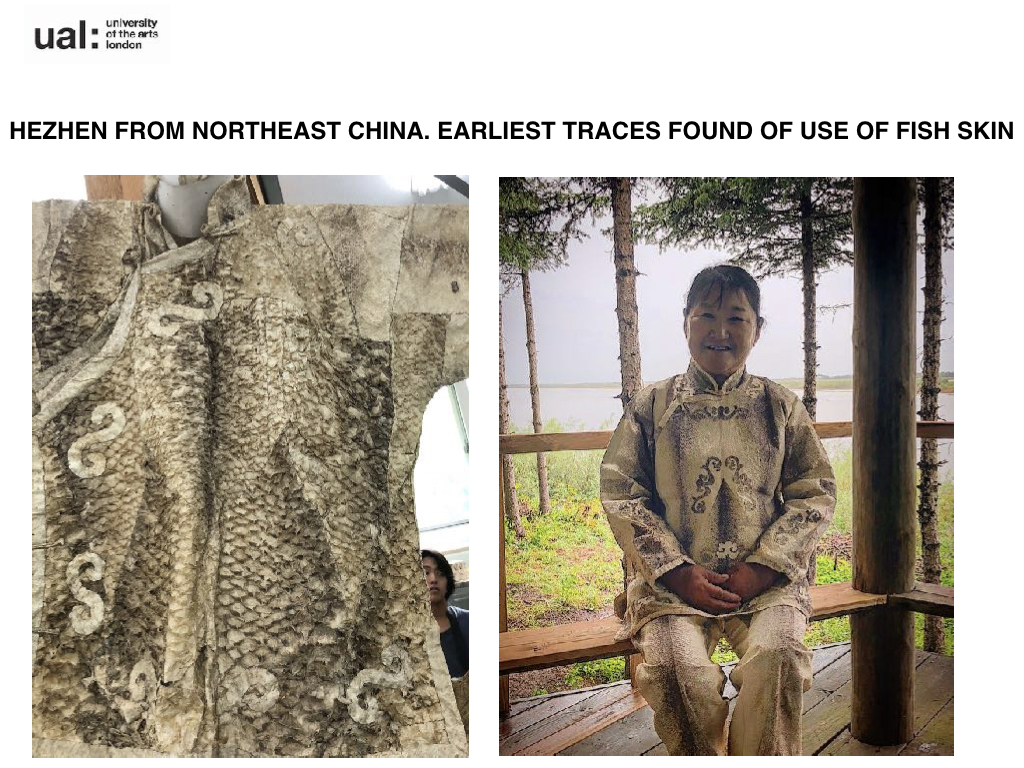

Another important aspect of the project is the indigenous traditional knowledge of fish skin. Historically, there have been many indigenous communities in the Arctic that used fish skin to dress themselves. For a lot of different communities living by the sea, ocean or river, fish was what they ate and used as a material to dress themselves.

Unfortunately, there are many reasons why fish skin craft is about to disappear. For example, in China, overfishing and water pollution has led to the decline in fish stocks. The constructions of dams have also caused significant damage to fish populations.

For a lot of the indigenous peoples, they have turned to farming or tourism for work and they also now have access to raw materials like cotton and silk. For these reasons, the use of fish skin in indigenous communities have now become reserved only for regalia or garments for rituals and festivals.

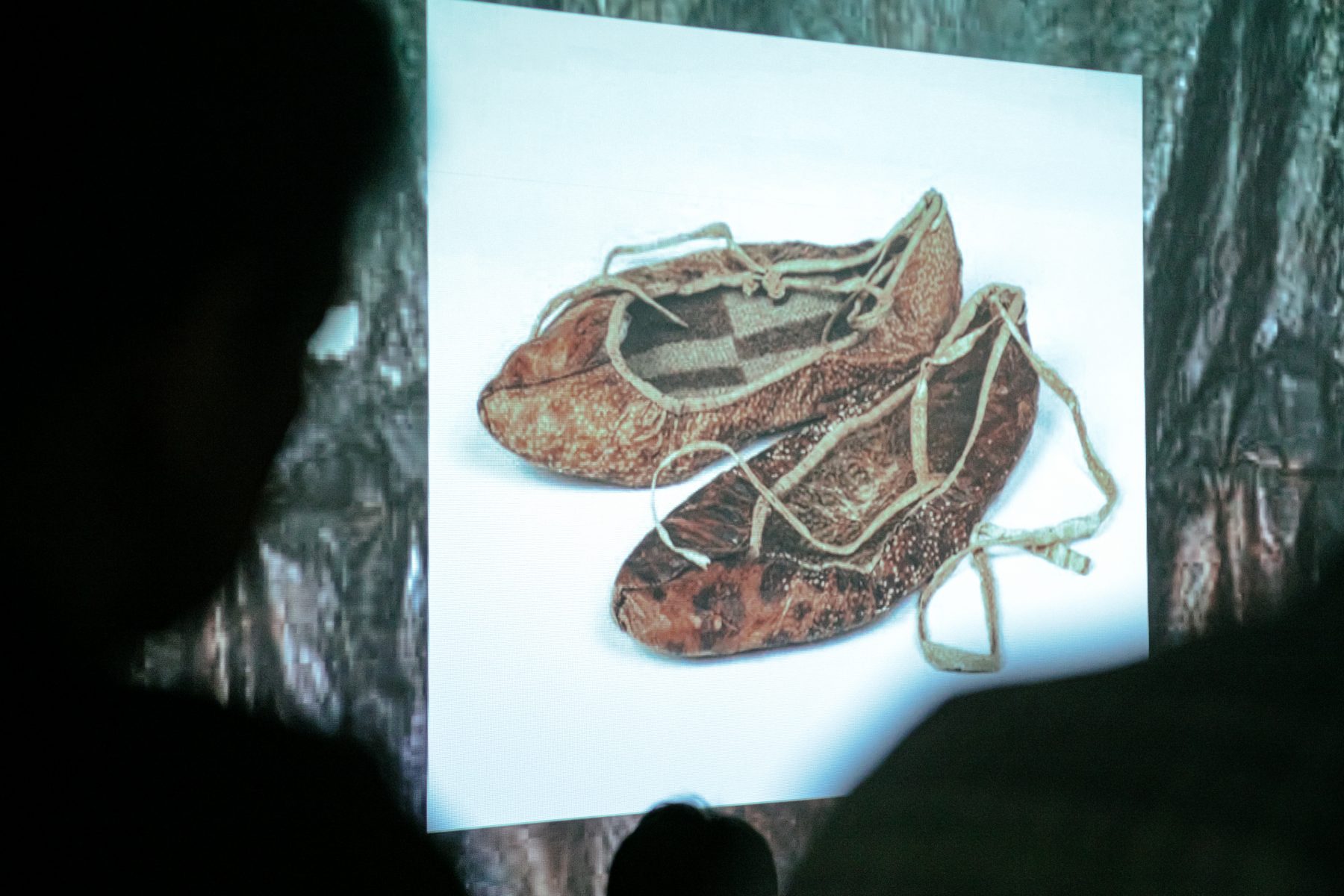

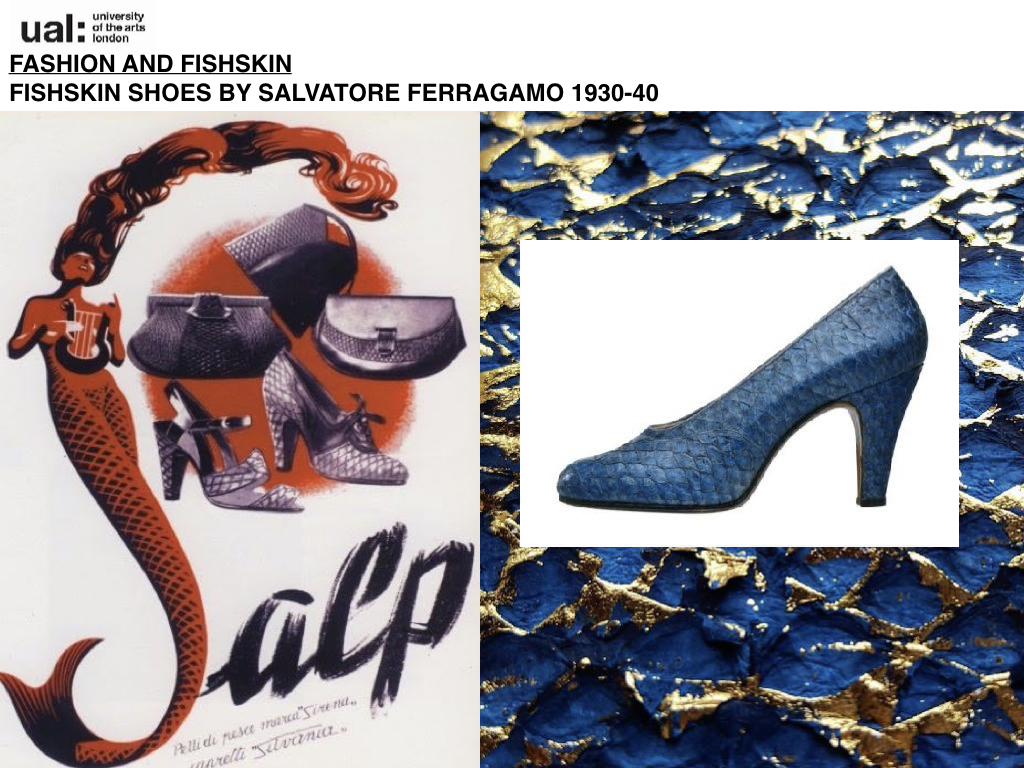

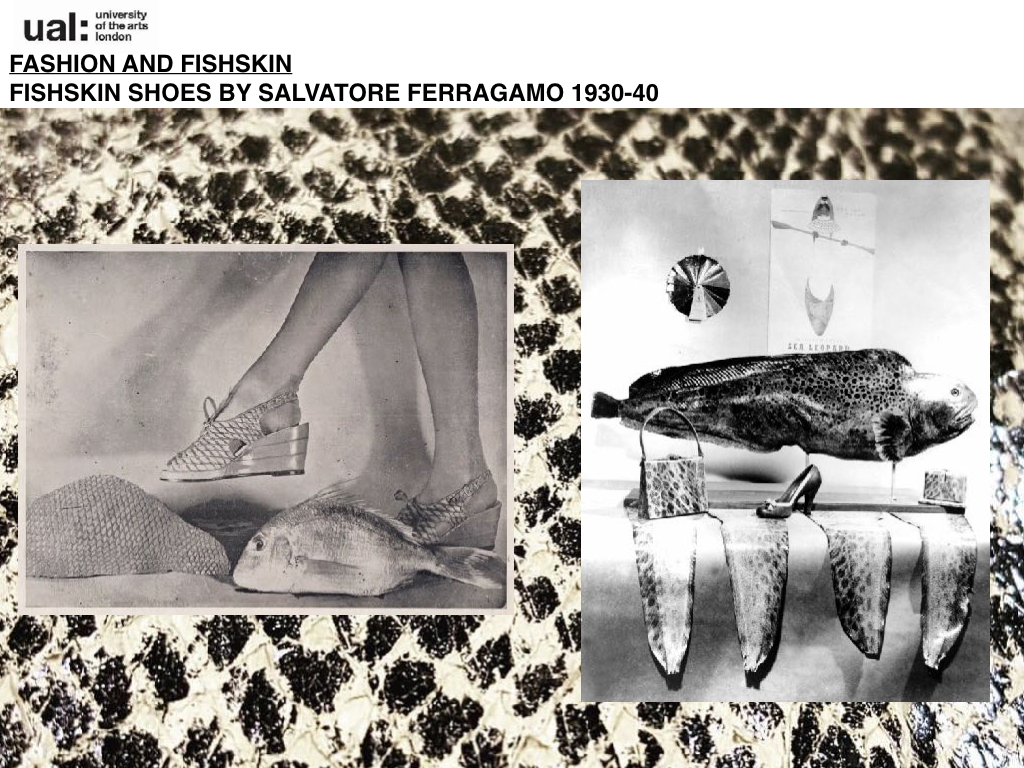

When he arrived in Italy, the country was right in the middle of the World War II, under Mussolini’s rule. This meant that it was difficult for raw materials to come into the country. So he looked around in search of alternatives and saw the fisheries from north of Italy. He then developed a new technique to tan fish leather.

This was in the 1940s. He was an incredible revolutionary, who was not only a designer but also a technician. And we can see some of the beautiful shoes that he created at that time. There is a great exhibition right now called sustainable fashion, in Florence at the Ferragamo museum, and some of these shoes are on display now. There were also some great advertising campaigns to go with it, which showed the fish that the leather was made from. These were very successful at the time. There are other brands who have experimented with the use of fish skin.

On the left, you have the Brazilian brand Osklen. They work with Nova Kaeru who developed fish skin from the Amazonian fish, Pirarucu. And pictured on the right is a pair of Nike trainers made with perch skin from Atlantic Leather.

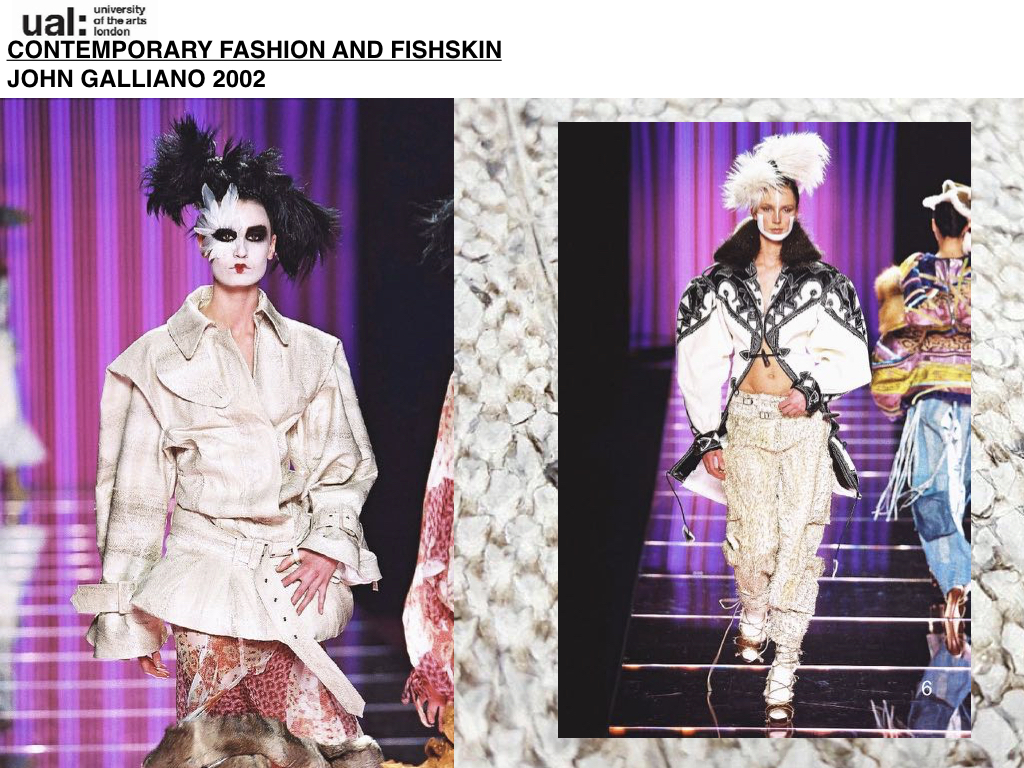

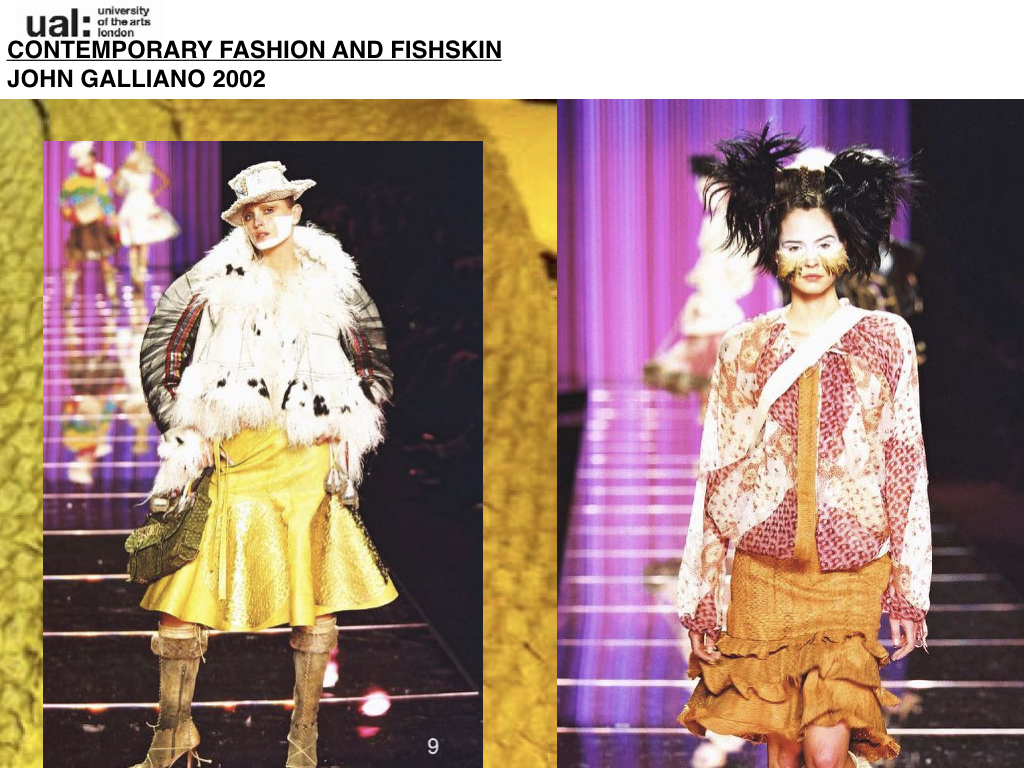

And you might be wondering, why are you so obsessed with fish skin? Back in 2002 when I was the head of the studio at John Galliano and also working for Christian Dior, we did a show, which was actually inspired by a family of Eskimo traveling to Paris in 1950s. Galliano was always so innovative about finding new materials and getting new ideas. And he sent us to Première Vision to source some fabrics. The head of the fabric department and I came back with all these salmon and perch skins to try and inspire him, which was always so difficult to do. That was quite a good thing that we came up with. John loved it, and we used it all over the collection. In the image, you can see a salmon leather jacket on the left, and a pair of perch trousers on the right.

Here you can see a salmon skirt on the left and perch skirt on the right. We also used fish skin for accessories. So, this is where my love of fish skin started originally.

These are samples of other work I have made recently, testing digital printing on salmon leather. You can see how similar it looks to snakeskin, which leads me to think that the fashion industry could easily make the switch to fish and leave snakeskin behind. I also have different samples of digital prints with our water-based inks, foiling and laser etching techniques, and laser cut designs.

The following slides show a project that is very dear to me. My job is to work with fashion students in higher education. These are fish skin workshops that I have organized along with other university teachers from different fields all around the world. Pictured here is the first one that we hosted in Iceland. I’ve brought together incredible students from top fashion universities in Northern Europe, like Central Saint Martins in London, the Royal Danish Academy of Art in Denmark, Aalto University in Finland, the Swedish School of Textiles in Boras in Sweden, and Iceland Academy of Arts, to share the techniques of fish skin. I believe the students are the future and once they are equipped with the knowledge and techniques, they are the ones who can make sure the craft does not die.

The second workshop was held in Japan at Nibutani Ainu Museum in Hokkaido. Again, the idea was to gather students from different universities, such as Kyoto Seika University, Bunka Gakuen University in Tokyo, and Osaka Bunka Fashion College, to learn the technique of making salmon skin boots. I then developed a third workshop in Heilongjiang province in the Northeastern part of China with the Hezhe indigenous community, who also tan and use fish skin.

I am always interested by what the students create after participating in the workshop.

One student created her own textiles with naturally dyed fish skins that she wove. Another student who had used fish skin before, went to the fishmonger in London after the workshop and created his own garments for the fashion show. There was also a student who paired up with a member of the Hezhe community and crocheted fish skin for her final collection. A student from Iceland who comes from a family of fishermen, also made a collection that combines embroidery and different men's wear materials with fish skin.

That concludes my presentation. I’m happy to answer any questions you may have. Thank you for your attention.

As Elisa-san talked about in her presentation, sustainable practices in fashion is at the core of this project. In the UK, well-known department stores and other major retailers have declared they will no longer carry products made with exotic leather. This has been reported in the news so some of you in the audience may already be aware of this initiative. It’s difficult for those of us in Japan to understand the urgency, but in the European fashion industry, designers are faced with a pressing problem of not having places to sell their exotic leather products. I imagine retailers outside of Europe will follow this trend and I’m sure it will reach Asia and Japan in the near future. Based on this shift, there is now a market for fashion design and manufacturing that uses alternatives to exotic leather. Kokita-san, is it fairly common in fashion for consumers to demand ethical practices from designers?

Fashion is not just about making clothes. It’s also a means of self-expression and a medium to share the depth and richness of your identity, but it shouldn’t only be about the individual ego or the quality of materials. I think it’s important to recognize that environmental and social awareness are valued in fashion. As educators, we need to learn about the relevant issues alongside students, and create places to generate those values.

The other thing I want to mention is that in Kyoto, dip-dyeing is almost exclusively done with synthetic dyes (chemical dyes). This might be unexpected, but for more than 150 years, the textile dyeing techniques in Kyoto has developed around the use of synthetic dyes. When they were first brought into Japan in large quantities from Europe and North America during the Meiji era, Japanese people were surprised by the vibrance, colorfastness, and variety of hues compared to plant-based dyes, which were the mainstream at the time. Particularly within Kyoto’s textile dyeing industry, there is a long lineage of artisans who mastered the use of synthetic dyes in traditional processes through trial and error. Setting aside for a moment the question of whether we should be using chemical dyes, textile dyeing in Kyoto went through a remarkable evolution over the past 150 years.

In our fish skin project, we have only used plant-based dyes so far. This is because the project stemmed from environmental and ethical concerns. But for most textile dyers in Kyoto, including Matsuyama-san, the dyes they use are normally synthetic.

With these two points in mind, I'd like to move on to a discussion about the specifics of dyeing fish skin. Earlier, Elisa mentioned that fish skin is a strong and durable material. Initially, this came as a surprise for me because I was imagining the flimsy salmon skin that you often eat for breakfast. During my visit to Iceland, I had the opportunity to feel the textures of some of the tanned fish leather, and they reminded me of snakeskin or crocodile skin.

We brought some fish skin samples today to share. These are the pieces that Matsuyama-san dyed. As we saw in the photo earlier, the color is very vivid immediately after dyeing, but as time passes, it becomes more muted like this.

One thing I’d like to ask Elisa is about her earlier comment on Atlantic Leather in Iceland. You said it’s extremely important that they are a family-run handcraft company. When we first visited Matsuyama-san's workshop in Kyoto together, you said the same thing.

You have been working to bring in family-run businesses and handcraft to this cutting-edge research. In the context of the fashion industry, where do you situate this move to envision our collective future through the lens of traditional handcrafts from around the world?

First, Iceland is concerned with the future direction of the country’s industry. As one of the leading fishing nations in the world, they also discard large amounts of fish skin during processing. If they could turn fish leather into a viable product, it would address both the ethical and environmental concerns in one fell swoop, while also generating profit.

Second, the fashion industry is urgently seeking a substitute material for exotic leather. In recent years, major department stores and retailers have stopped carrying products using exotic leather. But that doesn’t mean the demand for materials with similar textures has diminished. Fish skin is a promising candidate as a replacement for leather with scales.

Third, workers in leather processing plants are facing unjust labor environments. We must protect the workers’ rights and rethink the environment where proper transactions can take place to provide fashion materials.

Finally, Kyoto can take this opportunity to innovate its textile dyeing techniques that has historically catered to the kimono industry and specialized in silk. This is a challenge for those involved in this craft.

This endeavor carries the hopes and expectations of numerous contributors and partners. One of the many institutions that are participating in this project is the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences in Israel, which conducts environmental research. Their concern is that using fish skin could destabilize the marine ecosystem. Their role is to oversee the fish skin research and make sure that what began as a project to develop a sustainable alternative to exotic leather, does not cause new environmental problems in the process.

Elisa-san, what do you foresee as the outcome after four years?

We are also in contact with researchers who study seafood processing. Earlier, Elisa mentioned that more than 50% of the fish capture produces 32 million tons of waste. So how do we collect this large amount of waste for use in fashion? Unlike the meat-processing industry where the processing plants are concentrated in certain areas, seafood processing plants are usually scattered, which makes it difficult to source byproducts in large batches. In Japan, the waste from fish processing, including the skin is pulverized to make fertilizers or feed for farmed fish, making the procurement of domestic fish skin all the more difficult. If we are to think of fish leather production as an industry, we also have to think about the costs. Oftentimes, being ethical alone is not enough. We need to examine its financial viability as well, given that the results of this research will eventually be turned into a business.

More than anything, this research brings a lot of excitement, and it holds a lot of promise. When I first heard from Elisa-san and Kokita-san about a project to naturally dye salmon skin that has been tanned by hand, I thought it sounded very fun! My first thought was not about sustainable development goals or what it would mean for a sustainable society—I was simply excited by the concept. I hope we were able to share that excitement with you today. I plan to organize meetings in the future to periodically report on the progress of this project. I would like to invite everyone to follow along and join us on this endeavor.

There’s more to say on this topic but I think our time is up. We’ll end part one here.

Thank you.